Since its independence in 1971, Bangladesh’s journey has been riddled with enigma.

On the one hand, the country has achieved remarkable successes in economic growth and some social indicators, while on the other, it has fallen short, by far, of establishing an inclusive political system, and it has increasingly moved away from democratic principles in recent years.

Even as its geopolitical significance has increased, whether it will be able to benefit from it remains an open question.

As the country celebrates its golden jubilee, it is worth recalling that when Bangladesh emerged as an independent country between India and Myanmar, it drew little attention in the international media, and far less from the international community.

The easy availability of weapons because of the war of independence from Pakistan made some people worried that anarchy would follow. A dire prediction that it would be “the international basket case” was echoed by many.

But Bangladesh defied these predictions and confounded analysts. It not only survived, in many ways it thrived.

Today, Bangladesh is being observed closely by international actors – often drawing praise for its role on the global stage – and can hardly be ignored. In recent times, economic growth, political twists and turns, and geopolitical significance are the three reasons Bangladesh receives attention.

The slow but steady transformation of the country from an agriculture-based to a service-oriented economy, from an aid-dependent economy to a participant in the global supply-chain, and from a rural country to an urbanized society, is testimony to the resilience of its people in the face of many odds – natural and human-made.

Yet, as the nation marks its 50th year, its propitious journey to establish an inclusive political system has been reversed; authoritarianism is on the rise.

A thriving economy

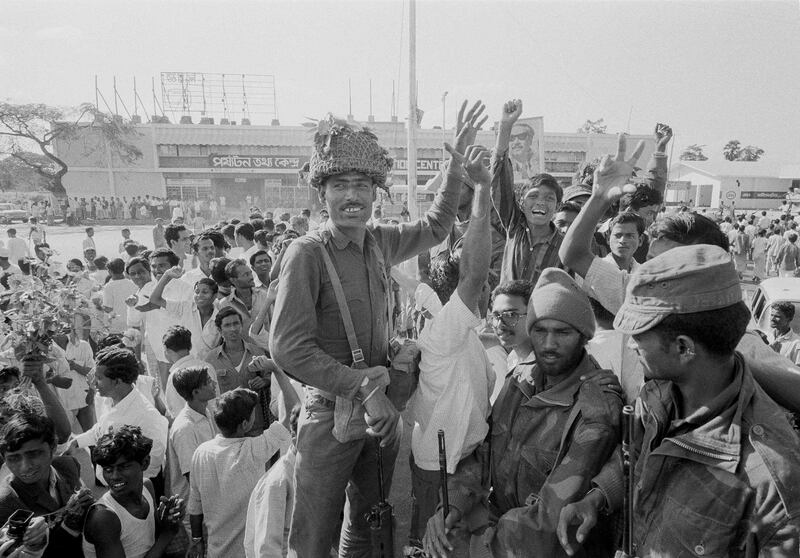

In the first two decades of its existence, the 1970s and 1980s, Bangladesh became synonymous with disasters – natural and political – in the international media. As famine, periodic floods and cyclones devastated the country, economic progress was slow at best, and political upheavals, including repeated military coups and assassinations of leaders, were frequent.

Despite a popular dream of a democratic, inclusive Bangladesh, the country was marred by civilian and military authoritarianism.

Yet, it was during this tumultuous time that the country became known for models that uplift the poor and disadvantaged. These include the microcredit movement of the Grameen Bank, and health and education programs of the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC), the world’s largest non-governmental organization.

Integration with the global economy came in various ways, including through short-term labor migration to the Middle East and Gulf states, and Southeast Asia, along with claiming a space in the global supply chain by becoming the second largest producer of readymade garments.

By the end of the nation’s second decade, a social transformation became palpable – as more women began to enter the formal economic sector and labor market, urbanization picked up speed and the economy became more globalized.

With the beginning of democratization in the third decade, not only did the political scene start to change, but Bangladesh’s economy began to take off. The country’s GDP growth continued to be high in the third and fourth decades.

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, the economy had been growing at more than 6 percent for more than a decade, according to official statistics. This growth was matched with developments in social indicators, for example, a rapid decline in maternal and child mortality along with the expansion of education, particularly for girls. Bangladesh outpaced many of its neighbors in achieving these goals.

These successes enabled the country to graduate to a Lower Middle-Income Country in 2015. In addition, it is set to graduate from Least Developed Country (LDC) to Developing Country in 2026.

A faltering democracy

Still, the successes were not unblemished, as corruption became endemic. State resources were being used for maintaining a clientelistic network rather than providing for the public good, and economic disparity as measured by the Gini Index increased.

The most important marker of these two decades was the mismatch between economic growth and political development – the country continued to experience bad governance and acrimonious, violent politics, while the economy thrived.

Yet, a de facto two-party system in politics allowed a fragile democracy to survive. Regular fair elections, alteration in power, freedom of speech and assembly, the presence of a vibrant civil society and promise of an independent judiciary created an opportunity for citizens to participate in politics and let their voices be heard. Institutional weaknesses notwithstanding, accountability mechanisms were in place.

But the political situation began to change in the middle of the 2010s, the fifth decade of the nation’s existence, as political rivals began to consider each other mortal enemies. Ideological opponents were viewed as existential threats, pernicious polarization was deliberate and schisms were cultivated. The feeble democratic institutions were further weakened through constitutional and extra-constitutional measures.

These paved the way for the return of the military to power, albeit under a civilian guise. Although the power was handed back to political leaders through an election, Bangladesh subsequently witnessed heightened executive aggrandizement, concentration of power in the hands of a single individual, repeated manipulated elections, enhanced persecution of the opposition, shrinking space for freedom of expression and the decimation of civil society organizations.

A global role

For a long time, Bangladesh’s role on the global stage was limited, except for being the second largest contributor to the United Nations Peacekeeping Forces. At independence, its foreign policy orientation was marked by its close friendship with the Soviet Union. The ideological leaning of the founding leaders and the supportive role of the USSR during the war of independence prompted this preference.

But Bangladesh took a decisive turn toward the West in 1975 after a military takeover. This policy has continued for decades with slight twists and turns.

In the last decade, India’s influence on Bangladesh increased as it created a hegemonic relationship with the incumbent Awami League, which returned to power in 2009.

However, as China’s ambitions to become a global power began to manifest in the 2000s, its focus turned to South Asia, including Bangladesh, and Beijing and New Delhi began vying to extend their influence in the country.

Although India remains closer to the incumbent Bangladeshi government, at least politically, Bangladesh has opened its door to China, and the relationship has warmed.

With growing interest by the United States in the Asia-Pacific, the contestation will be more intense in coming days.

Bangladesh at a crossroads

At its 50th year, Bangladesh stands at a crossroads.

In politics, it faces the choice between pursuing the current pathway of a non-inclusive system of governance. This could lead to further shrinking of space and restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, or reverse the current course to return to democracy.

In the economy, the choice is between continuing growth for a few, or developing a system that addresses the disparity and leaves nobody behind.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, and the president of the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of Illinois State University, the Atlantic Council, the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies, or BenarNews.