Plans by the Chinese Communist Party to construct a dam and hydropower project on the Yarlung Tsangpo River, which becomes the Brahmaputra River downstream, could create "life and death" concerns for Bangladesh, a local hydrology expert said.

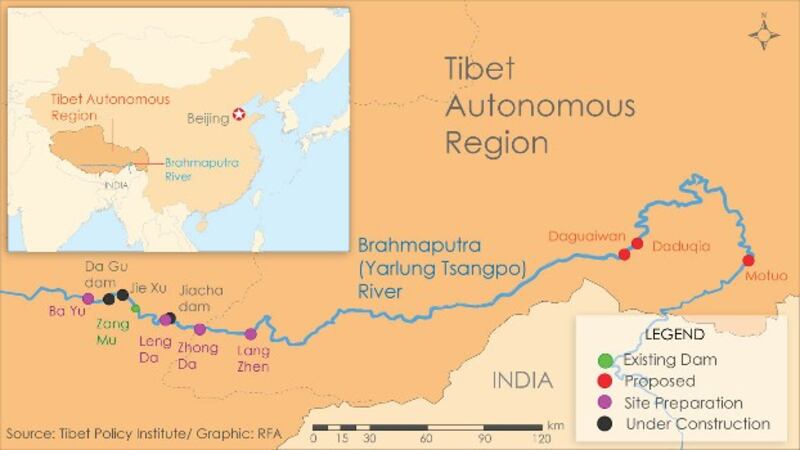

The plans to create up to 60 gigawatts of hydropower capacity was a "historic opportunity" to boost China's clean energy plan as well as the country's water supply security, China Energy News quoted Yan Zhiyong, the chairman of the state-owned Power Construction Corp., as saying. The Chinese Communist Party (CPP) has listed "developing hydropower resources on the ... Yarlung Tsangpo river" in its Five-Year Plan running from 2021-2025.

In Bangladesh, the former chief hydrologist of the Water Development Board said the Brahmaputra was responsible for at least 65 percent of the water flowing into the country. The river enters Bangladesh from India and flows out at the Bay of Bengal in the south.

“If the water of this river is diverted from the upstream, it would be a question of life and death in Bangladesh,” Shawkat Ali told BenarNews.

“Following China’s footprint, India may also construct dams and would probably divert water from the river. If it happens, then we would face huge uncertainty over getting water from the Brahmaputra,” he said.

Elsewhere, environmental groups and Tibetan rights activists told Radio Free Asia (RFA), a sister entity of BenarNews, that such projects wreak environmental havoc and have a severe impact on downstream water supplies.

"Scientists have warned that constant construction of hydropower dams will lead to earthquakes, landslides and also submerge land and forests under water, which will endanger wildlife," Zamlha Tenpa Gyaltsen, an environmental analyst at the Dharamsala-based Tibet Policy Institute, told RFA in a recent interview.

"It may also lead to either floods in the area or water shortages. The bottom line is it will cause huge environmental destruction," Zamlha Tenpa Gyaltsen said, adding, "It will seriously impact Arunachal Pradesh and Assam in India, through which the river flows."

Brian Eyler, Southeast Asia program director at U.S-based think tank Stimson Center, said details of the dam's specifications and location are unclear.

"[This] announcement has already drawn criticism from downstream countries, particularly India," Eyler said. "Upstream dams on the Brahmaputra impact downstream seasonal hydrological cycles which hold important cultural significance and impact local and national economic activities."

"This new dam was announced with minimal prior consultation with downstream countries, nothing new for China's treatment of downstream neighbors," he said.

Unprecedented downstream impact

Eyler said the project was just one part of a massive dam-building program in the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra, Mekong, Yangtze and Yellow rivers that would have an unprecedented impact on everyone downstream.

Meanwhile, anti-hydropower groups said China's rivers were already at a saturation point after a dam-building boom that included the construction of the Three Gorges Project and other giant hydropower plants on the Yangtze and its tributaries.

Zamlha Tenpa Gyaltsen said there could be a more political motive behind the project.

"I believe that behind these road and hydropower projects, the Chinese government's main intention is to resettle Chinese people in Tibetan areas," Zamlha Tenpa Gyaltsen said.

A U.S. government-funded study published earlier this year showed that a series of new dams built by China on the Mekong river had worsened drought in downstream countries, although Beijing disputed the findings, saying it could add up to 350 more gigawatts of hydropower.

In India, the dam project has already raised fresh concerns.

Jagannath Panda, a research fellow at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defense Studies and Analyses in New Delhi, said Indian policymakers are concerned that not enough information is being shared about China's doings upstream.

"I think it is a genuine concern for India for a long time," he said. "India would ideally expect that China, before doing any kind of construction on the dam … would and should consult India."

China-South Asia trust at low point

Panda said information should be transparent and not shared selectively.

"This information and data are crucial for the progress of agriculture, for the progress of people's livelihood," he said.

Farwa Aamer, a director at the EastWest Institute South Asia program, said trust between South Asian countries and Beijing was at a low point.

"A lot of things don't work out because there is mistrust," Aamer said. "So anything that one country does out of mysteries the other country is likely going to feel threatened."

The experiences of downstream countries through which the Mekong runs is a case in point, Eyler said.

"Data provision [regarding the Mekong basin] is still a trickle of information compared to what is needed to improve outcomes downstream," he said. "China often doesn't notify countries of new dam developments on the Mekong: a case in point is the Tuoba Dam on the upper Mekong in Yunnan province which began construction earlier this year with zero notification."

11 Mekong dams

China’s 11 Mekong dams have had a severe impact on hydrological cycles downstream, restricting the water flow at times of drought, Panda said.

"China's official discourse on these actions is that upstream dam restrictions prevent floods downstream and reduce drought by releasing water when needed," Eyler said. "But ... there is absolutely zero evidence that China's upstream regulations reduce floods and improve drought conditions."

Along the Brahmaputra, there is additional cause for worry.

A recent study by the scientific journal Nature Communications found that destructive flooding likely will happen along the river more frequently than previously thought, owing to a miscalculation of the baseline in recent years.

United Nations figures showed that around 30 million people in Bangladesh were exposed or living close to flooded areas as of July 2020.

Bangladesh and other countries know little about what China’s actions on the Brahmaputra, according to Ainun Nishat, a water resource and climate change specialist who is a professor emeritus at Bangladesh’s BRAC University.

“This is very difficult to predict the behavior of the Chinese central government. They can easily upend their previous decision and go for implementing the plan of diverting the river to Inner Mongolia,” Nishat told BenarNews.

He noted that if the dams were to be used solely for producing electricity, China’s southern neighbors India and Bangladesh should not be concerned about water.

“This is because unless they release the water, they cannot move the turbines to generate electricity. But if they divert water in addition to producing electricity, then danger awaits us,” he said, noting that India had built its own dams on the river.

“Bangladesh should work closely with India to ensure that the lower riparian countries get their due share of water of the Brahmaputra,” he said.

China controls the upstream waters of seven huge rivers – the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy, Salween, Yangtze and Mekong, which flow into Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam.

Kamran Reza Chowdhury in Dhaka contributed to this report.