Bangladesh’s birth as a nation in 1971 was violent, coming out of a war partly ignited by the then-Pakistani military government’s refusal to honor the results of a democratic election.

Fifty-two years after East Pakistan broke free and became Bangladesh, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina – the daughter of the country’s founding father – and her party seem poised to clinch a lopsided victory for a fourth consecutive term through the ballot box.

Government critics and the opposition, however, warn that next month’s general election will essentially be another undemocratic exercise in a nation with a long record of dubious polls. As its own nation, Bangladesh has failed to institute an independent election system that’s credible enough to satisfy domestic and international observers, critics say.

“Even after 52 years of independence, we still lack an electoral system acceptable to all. This is extremely disappointing,” Mujahidul Islam Selim, a Bangladeshi freedom fighter in the 1971 war and a veteran politician who heads the Bangladesh Communist Party, told BenarNews.

“Politics has morphed into merely a means of plundering public wealth. To sustain this plunderage, no one wants to risk going out of power.”

Hasina inherited the reins of the Awami League party years after her father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was assassinated during a military coup in 1975. In the months leading up to the Jan. 7 election, she and Awami officials have refused to give in to the opposition’s main demand that her government step aside to allow a neutral caretaker government to oversee the polls to guarantee that they be free and fair.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party, which leads the opposition, has staged mass street demonstrations and transportation strikes in 2023 to force Hasina to step aside. But Hasina and her party have not buckled under this pressure. The BNP has now opted to boycott the polls after the Awami League refused to budge on the caretaker government issue.

On Dec. 16, Bangladesh celebrated the 52nd anniversary of its victory against the Pakistani military in the 1971 war for independence, but criticism about the state of democracy in the South Asian nation of 160 million persists.

During Hasina’s uninterrupted rule as PM for the past 14 years, Bangladesh’s economy posted impressive growth, but that progress shrunk after the COVID-19 pandemic and through a steep rise in oil prices following the Russian invasion and war in Ukraine.

Critics, including international human rights groups, have accused her government of becoming increasingly authoritarian and committing rights abuses and violations, such as jailing critics and carrying out extrajudicial killings and state-backed enforced disappearances. Government officials have adamantly rejected such accusations as false.

Next month's polls will be the 12th general election in Bangladesh's history as a free nation, but some observers are predicting that the polls will seal Hasina's autocratic rule.

Out of the 11 previous general elections, only four were considered to be relatively free, fair and uncontroversial because they were shepherded under a non-partisan caretaker system.

“The rest of the elections were very controversial, domestically and internationally,” M. Sakhawat Hossain, a former election commissioner, told BenarNews.

All of the four elections that were overseen by a caretaker administration delivered a victory for the opposition, whereas the seven polls under a partisan government always resulted in a landslide for the incumbent.

The Awami League government removed the provision for a caretaker government from the constitution in 2011 based on a partial reading of a Supreme Court ruling. The two elections held since then have been contentious.

In 2014, the opposition led by the BNP boycotted the elections, allowing the Awami League to return to power virtually unopposed. The boycott was so widespread that the Awami League faced no rival candidates – not even from independent ones – in more than half of the parliamentary seats.

In 2018, the opposition did take part in the vote, but the ruling party and its allied partners secured more than 95% of the seats amid reports of extensive fraud and intimidation.

Citing this experience, the BNP refused to participate in the upcoming Jan. 7 election.

The government responded to the BNP’s protest rallies and escalating strikes and transportation blockades – which often disintegrated into violence – by arresting tens of thousands of its members, including senior figures.

In 1970, when Bangladesh was a geographically detached region of Pakistan, the Awami League headed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – widely regarded as the leader of the Bangladeshi independence movement – captured the majority of Pakistan’s federal legislature.

However, the Pakistani junta, led by Gen. Yahya Khan, refused to recognize the Awami League’s right to rule Pakistan. As negotiations to end the stalemate extended to March 1971, the Pakistani military launched “Operation Searchlight” in what’s now Bangladesh, targeting mainly Bengali civilians.

As many as 3 million people are believed to have been killed in the war, which ended in the defeat of the Pakistani military on Dec. 16, 1971.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who had been jailed by Pakistan early on during the war, returned from a Pakistani prison to take the helm of the newly independent country as its president in 1972.

But the tenure in power of Bangladesh’s founding father drifted into autocratic rule.

The election in 1973 – the first in independent Bangladesh’s history – saw Rahman’s party win all but seven seats in the 300-seat parliament.

In 1974, he formalized the country as a one-party state by banning all other political parties and most of the press.

After his assassination in a coup the next year, a military government in various iterations ruled the country for the next 16 years. During those years, elections in Bangladesh lacked legitimacy and were widely seen as a rubber stamp to gain authority.

Elections under the military rulers in the 1980s sowed deep-seated suspicion among the public about the electoral system, according to Abul Kashem Fazlul Haq, a retired professor of Dhaka University.

“But even during the military rule, the distrust was not as widespread as it is today,” he told BenarNews. “This proves that we are deteriorating gradually as a nation.”

‘Caretaker’ system

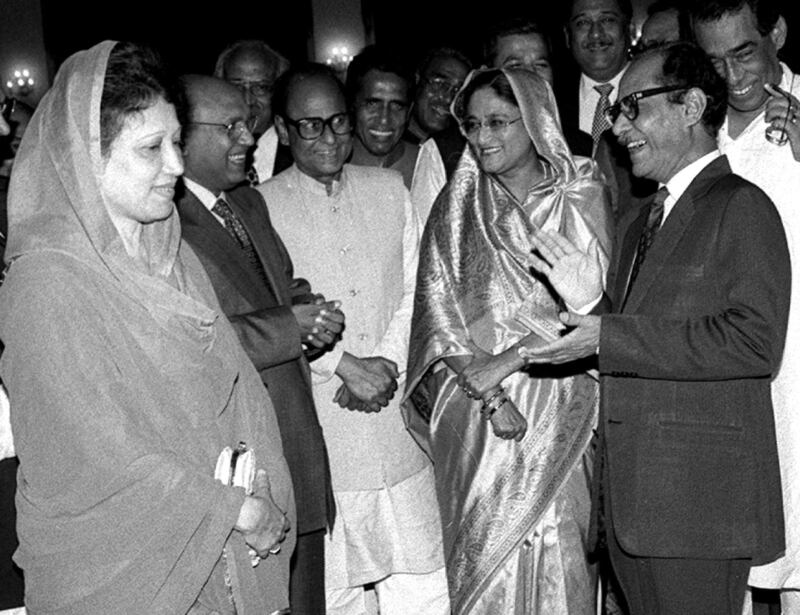

In 1990, the Awami League and the BNP banded together to end the military rule of Gen. Hussain Muhammad Ershad.

Both parties then agreed to take part in an election under an interim government headed by Shahabuddin Ahmed, a widely respected chief justice of the Supreme Court.

The election returned a narrow victory for the BNP.

But as the BNP’s tenure neared an end, the Awami League began to call for a permanent non-partisan system of electoral government, citing alleged rigging in parliamentary by-elections.

The BNP rejected the demands and went ahead with holding a one-sided election in February 1996 where its candidates won in all but 11 seats.

However, amid violent protests from the Awami League-led opposition and under mounting pressure from a large swath of civil society, the BNP-led government gave in to pressure to codify the caretaker system into the constitution.

“The BNP should be credited for agreeing to launch the caretaker system in the face of demands from all opposition parties for an acceptable election process,” said Nazrul Islam Khan, a member of BNP’s top decision-making body and a veteran of the 1971 war.

Within a month, the BNP resigned from the government so that the newly formalized caretaker government could hold another election. Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League came to power through that election.

Five years later, in 2001, under a similar caretaker government, the BNP-led opposition coalition returned to power with a landslide victory.

But around 2006, the Awami League, which was then in the opposition, again raised accusations against the BNP government. It accused the BNP government of trying to manipulate the caretaker system by allegedly pushing for a loyal former chief justice to head the electoral government.

The judge soon declined to lead the interim government, but violence and clashes persisted.

In early 2007, the military intervened as parties failed to reach any consensus and helped install a technocratic government led by a former central bank governor.

That caretaker government didn’t limit itself to holding an election.

Instead, it launched ambitious reform programs and even arrested major political leaders, including Sheikh Hasina and BNP leader Khaleda Zia on corruption charges.

With its reform experiments largely failing after more than a year, the government decided to hold an election by releasing most political prisoners.

In that election in 2008, the Awami League returned to power with a thumping supermajority.

Three years later, the Supreme Court declared the unelected nature of the caretaker system unconstitutional, but carved out an exception for two more elections under the system.

The Awami League ignored the exceptions and removed the caretaker system from the constitution.

‘Both are to blame’

Today, many observers in Bangladesh view both parties as equally responsible for the credibility crisis facing the election system.

“The non-partisan caretaker government was introduced as an emergency measure, but because of the power-hungry mentality of the BNP and Awami League, this system became controversial,” said Mujahidul Islam Selim, the communist party leader.

“The BNP tried to manipulate the caretaker system to cling on to power and failed. But the Awami League succeeded. With its wholesale elimination of the caretaker system, the Awami League de-legitimized the entire electoral arrangement.”

But the Awami League and the BNP have wildly different interpretations of today’s crisis.

“After removing the caretaker system from the constitution, the Awami League has held the election process hostage,” said Nazrul Islam Khan, the BNP leader.

“The upcoming elections will be the last nail in the coffin of our election system.”

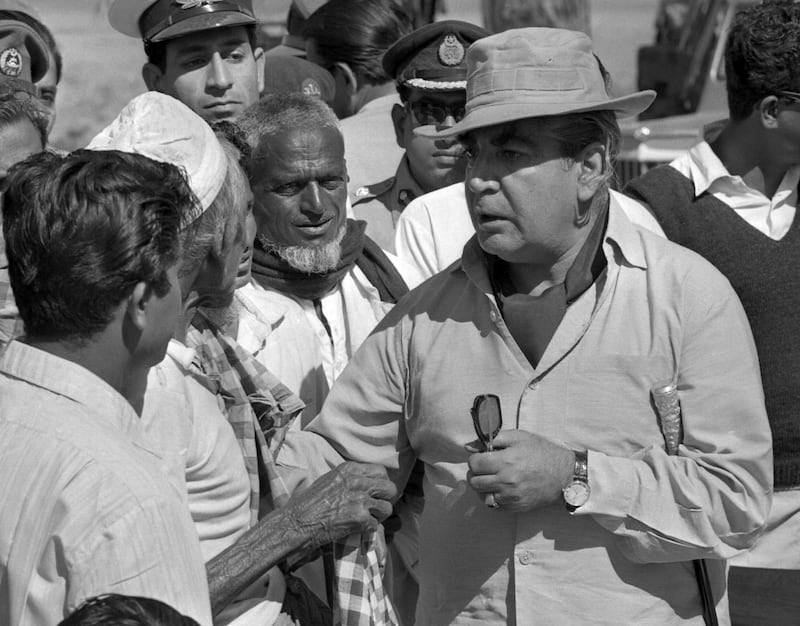

Shahjahan Khan, another 1971 freedom fighter and a member of the Awami League’s top political body, agreed that Bangladesh’s election system still faced debates.

But, he said, his party was trying to build a stronger electoral system by fighting against the BNP.

“The BNP is not a democratic political party,” he told BenarNews, referring to its boycott of the election. “Whatever they do does not matter to the people of this country.”