Violence and repression by Indonesian security forces have increased in the past two years in a part of Papua province where the government is planning to operate a massive gold mine, rights group Amnesty International said in a report released on Monday.

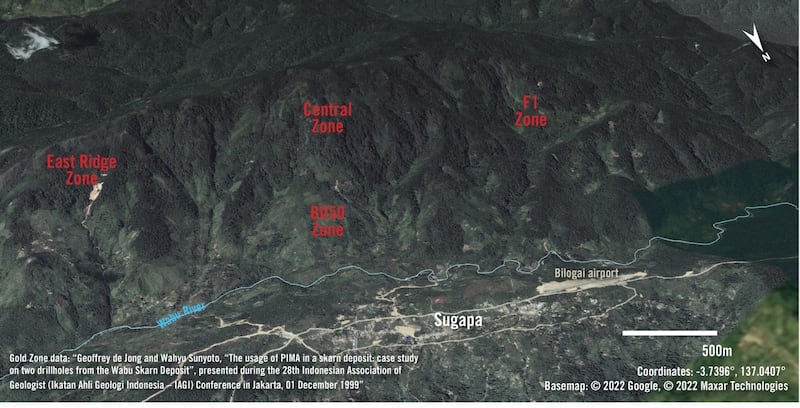

Indonesia’s state-owned PT Aneka Tambang Tbk plans to operate a gold mine in the Wabu Block in Intan Jaya regency, which is believed to have gold ore deposits of about 117.26 million tons, according to a 1999 survey by U.S. mining company Freeport-McMoRan.

In the report titled “Gold Rush,” Amnesty documented a dramatic increase in violence in the past two years, including cases of extrajudicial killings and greater restrictions on movement targeting indigenous Papuans, based on interviews with locals between March 2021 and January 2022.

“Intan Jaya regency has become a hotspot for conflict and repression,” João Guilherme Bieber, an environmental researcher at Amnesty International, said during a news conference releasing the report in Jakarta.

“It’s against this backdrop of violence, insecurity and fear that the Indonesian government plans to develop mining activities in Wabu Block, and that’s why we are concerned,” Bieber said via video link from Brazil.

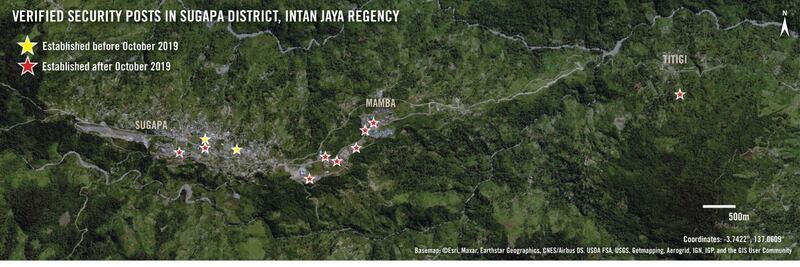

Amnesty said the growth of the security force presence in Intan Jaya – from two posts in 2019 to 17 currently – had been accompanied by an increase in unlawful killings, raids and beatings. Most of the new security posts are in Sugapa district, it said.

Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) officials in Jakarta and Papua declined to comment on the Amnesty report. However, Aqsha Erlangga, spokesman for the provincial military command, previously denied allegations of abuses by security forces against civilians, calling them hoaxes.

Amnesty urged Indonesian authorities to halt the gold mine plan, saying it risks fueling conflict and violating the land rights of indigenous Papuans.

The rights group said its study found an alarming build-up of security forces in Intan Jaya since 2019, with at least 12 suspected unlawful killings and other human rights violations carried out by Indonesian troops.

Separatist insurgency

Since the 1960s, Papua has been home to a separatist insurgency, while the country’s security forces have been accused of human rights abuses in counter-insurgency operations.

In 1963, Indonesian forces invaded Papua – like Indonesia, a former Dutch colony – and annexed the region that makes up the western half of New Guinea island.

Papua was incorporated into Indonesia in 1969 after a United Nations-sponsored vote, which locals and activists said was a sham because it involved only about 1,000 people. However, the U.N. accepted the result, essentially endorsing Jakarta’s rule.

In 2003 the Indonesian government divided the western half of New Guinea island into two provinces – Papua and West Papua.

Papuan human rights activist Yones Douw said health clinics, schools and government services have suspended operations in many remote parts of the province because of the conflict between the Free Papua Movement (OPM) and Indonesian troops.

“In the past, OPM used arrows and now they have firearms. When they clash with TNI, civilians have always been the victims,” he said at Monday’s news conference.

“A peaceful settlement will not be achieved as long as there’s no prosperity and people are hurt. The Papuan people have lost their faith,” he said, adding the Indonesian government “must have a dialogue” with those fighting.

“If they can sit together like they did in Aceh, why can’t they do it in Papua?” Douw said, referring to the peace talks between Aceh separatists and Jakarta, which were partly influenced by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami disaster.

Large gold reserve

Located south of the Sugapa district, the main town in Intan Jaya, Wabu Block could hold about 8.1 million ounces of gold, making it one of Indonesia’s five largest-known gold reserves, according to Amnesty.

The proposed mining area covers 170,500 acres – about the size of Jakarta, Amnesty said, citing official documents.

Papuans said they fear the loss of land and livelihood to the mining project.

“If there is mining, we will have no land for gardening; livestock will not get fresh fruit directly from the forest, and even our grandchildren will lose customary land,” Lian, a local indigenous man, was quoted as saying in an Amnesty statement.

Usman Hamid, Amnesty’s executive director in Indonesia, issued a statement with the report urging the government to consult the local population.

“People in Intan Jaya are living under an increasingly harsh and violent security apparatus that exerts control over many aspects of their daily lives and now their livelihoods are under threat from this ill-conceived project,” he said. “Simply put, Wabu Block could be a recipe for disaster.”

Bieber alleged Papuans had not been consulted about the mining plans.

“Indonesia has an obligation to consult them in order to obtain prior and informed consent regarding the plans,” he said during Monday’s news conference.

“We understand that under the existing conditions of insecurity, there are several obstacles to carry out a meaningful and adequate consultation process that is in line with international human rights standards,” Bieber said.

In interviews with Amnesty, residents said Indonesian security forces track their daily activities including going to the fields, buying groceries, or visiting other villages.

“When we go to town for shopping, we are asked where we go, which village we are coming from, where we live. Then after shopping, while we are going home, our stuff is checked,” Lian told Amnesty.

In some cases, security forces restrict the use of mobile phones and other electronics and detain locals with long hair over suspicion of ties to separatist rebels, the Amnesty report said.

Adriana Elisabeth, a researcher at Papua Peace Network, a conflict resolution NGO based in Papua and Jakarta, called on the government, the business sector and Papuans to sit together to resolve issues related to the planned gold mine.

“For Papuans, development is welcome, but they don’t want to be neglected as landowners,” Adriana told BenarNews.

“They are not against change and modernization, but it takes time, and they should not be exploited,” she said.