On a hilltop accessible only by hours traversing dense jungle on foot, the influential Kimko Jinipjo clan in Indonesia’s Papua region gathered for a rare ceremony called “Awon Atatbon” earlier this month.

For these indigenous people in Ha Anim territory – the local name for South Papua Province – this “pig feast” ritual is more than a celebration of cultural identity.

It is also an assertion of their ancestral land rights and a form of resistance against government-backed agricultural projects, resource exploitation and the mounting threats of deforestation.

“At its heart, Awon Atatbon is a cultural revival aimed at safeguarding ancestral lands through traditional practices, including songs, dances, rituals, and ceremonial performances,” Vincent Korowa, a young member of the clan, told BenarNews.

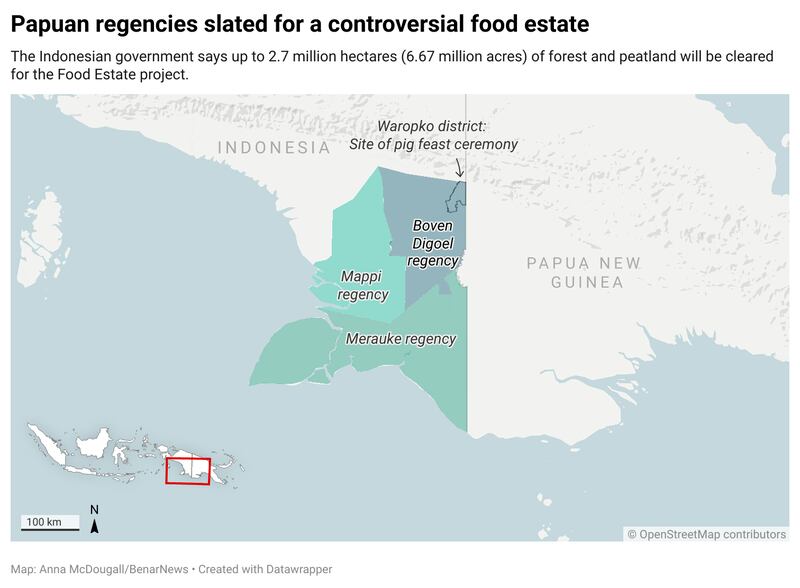

The hilltop village of Kurinbin is situated in Waropko, a district of Boven Digoel regency. Up to 2.7 million hectares (6.67 million acres) of forest and peatland in Boven Digoel, Mappi and Merauke regencies are slated to be cleared for a controversial food estate project, according to government data.

A land of stunning biodiversity and immense natural wealth, Papua is also home to one of the world's longest-running separatist conflictsbetween Indonesia and armed Papuan groups who want their own state.

International and Indonesian human rights groups say indigenous Papuans, a Melanesian people whose identity is closely tied to the land, face entrenched racism in Indonesia, economic marginalization and violence by security forces including extrajudicial killings.

In recent years, the Indonesian government has pushed controversial development initiatives, including the food estate program, which aims to convert vast tracts of forest, wetland and savannah into rice farms, sugarcane plantations and related infrastructure to bolster the country's food security.

Critics of the food estate say these projects overlook indigenous land rights, accelerate deforestation, and threaten the way of life of Papua’s native communities.

RELATED STORIES

[ Indonesia: Survey warning on Papua mega project appears to go unheededOpens in new window ]

[ A conservation treasure is threatened by Indonesian plans for food securityOpens in new window ]

Food estate programs in other parts of the country have been unable to meet production targets. In Central Kalimantan, rice, the primary crop, has failed to achieve expected outputs.

“We know that our ancestral land is constantly under threat. In the past, it was other tribes. Now, it’s people who want to establish large plantations,” Wilem Wungim Kimko, the host of this year’s pig feast, told BenarNews.

“When our land is taken, our ancestors’ spirits are disturbed, and we all suffer,” said Wilem, who as host is known as the “Big Man.”

The Awon Atatbon is held every seven to 12 years or when a Kimko Jinipjo clan leader is ready to host the elaborate event.

After three years of preparation, the clan this year welcomed hundreds of participants from other areas and clans to their ancestral hilltop village.

At the heart of the ceremony were the pigs, which were hunted by specially selected archers.

The “Big Man” then offered the captured animals to attendees at fixed prices, ranging from U.S. $320 to $640.

Once purchased, the pigs were cooked communally, using a traditional method of stone baking, alongside sago and vegetables.

This practice ensures that wealth circulates within the community, strengthening social and economic bonds.

“The feast is also a trading activity between the host and other members of the indigenous community,” Ponsianus Tarayok Kimko, the eldest living member of the Kimko Jinipjo clan and the leader of this year’s event, told BenarNews.

A ritual called “Oktang,” which is also part of the ceremony involved testing the resilience of the Big Man’s stilt house by dancing on its roof through the night.

Inside the one-meter-high traditional structure, 26 participants performed a ceremonial dance that embodied both spiritual devotion and a reaffirmation of cultural unity.

The guests invited to Awon Atatbon traveled from various parts of the Ha Anim territory, with some journeying from nearby Papua New Guinea.

They walked for up to two days across steep terrain, as they crossed rivers and scaled ridges to attend the ceremony.

“I traveled with my family from Kiunga in Papua New Guinea,” Magdalena, one of the attendees, told BenarNews.

“It took us nearly two days on foot. We spent one night sleeping in the forest. We came because we were invited – and because we are family to the host.”

Rituals, dances, and songs reinforced community bonds and territorial claims.

During the event, the boundaries of clan land were reaffirmed through natural landmarks like rivers and soil lines, and prayers were offered to ancestors for protection and future prosperity.

Anthropologist Cypri Jehan Paju Dale, who studies Papua indigenous politics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, sees ceremonies like Awon Atatbon as part of a broader movement to defend land and identity.

“Local communities in West Papua are working tirelessly to protect their identity, land, and forests,” Dale told BenarNews, referring to the Papua region of Indonesia.

“They do this not only by engaging with advocacy groups but also by revitalizing their own cultural traditions and articulating them in new ways.”

While the pig feast is one such example, another is the Red Cross Movement. As part of the latter, indigenous Christian communities plant thousands of red-painted crosses to block the expansion of large-scale plantations and mining projects.

Since its inception in 2014, the Red Cross Movement has planted more than 1,400 crosses across southern Papua.

While the movement adopts Christian symbolism, it draws deeply from indigenous values, sending a message that the land and forests are not vacant but living spaces that must be preserved.

As the Indonesian government continues to push its development agenda, the Kimko Jinipjo and other clans in Papua face growing uncertainty.

This year’s Big Man, Wilem, like many in his community, lacks formal identification or citizenship documents. Though unaware of the specifics of the government’s plans, he is keenly aware of the risks posed by food estate developments.

For his clan, the forest provides not just sustenance but cultural identity and spiritual guidance.

“Our ancestors communicate with us through signs in nature,” Wilem said.

“When the animals in the forest begin to disappear, it’s nature’s way of telling us that the land they inhabit is under threat.”

READ MORE

[ Papuans worry about new Indonesian leader Prabowo’s plan to revive transmigrationOpens in new window ]

[ Indonesia accused of subverting Pacific push for UN rights mission to PapuaOpens in new window ]