UPDATED at 12:10 p.m. ET on 2025-02-07

Indonesia’s ambitious push toward clean energy is facing new uncertainty after the United States again withdrew from the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit the rise of global temperatures from carbon emissions.

Much of the Southeast Asian nation’s energy transition has relied on partnerships with major economies, including the U.S., which has been a key player in financing climate-control programs.

But with Washington under newly reinstalled President Donald Trump stepping back, analysts warn that crucial funding streams could dry up, delaying efforts to close coal plants and build cleaner alternatives as Indonesia works toward its goal of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050.

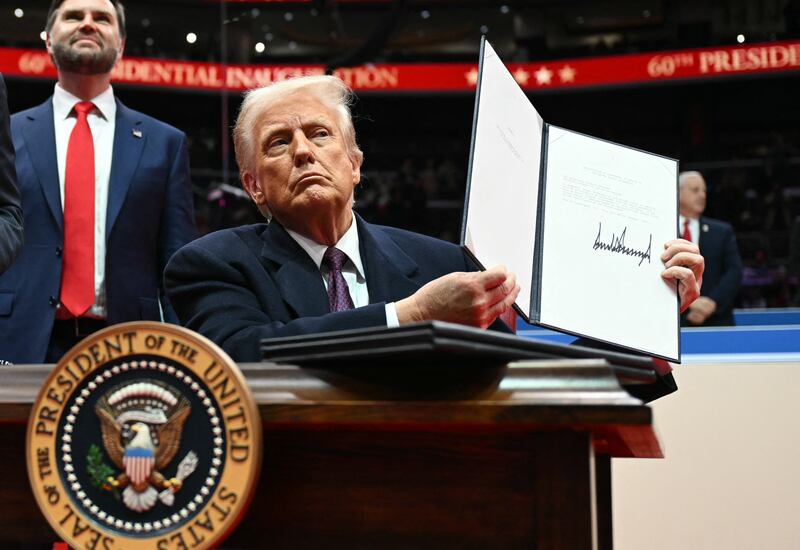

On the day he took office for a second time, Trump signed an executive order pulling the U.S. out of the landmark climate treaty.

“Indonesia as a developing country will be affected by reduced funding, especially if stricter regulations are imposed,” Mahawan Karuniasa, an environmental analyst at the University of Indonesia, told BenarNews. “Without U.S. involvement in the Paris Agreement, there is no adequate plan to support developing nations.”

Adopted in 2015, the Paris Agreement is a landmark global accord aimed at limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Major emitters, including the U.S., China and the European Union, pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support developing nations in their climate efforts.

But Trump’s Jan. 20 order directing the United States to again withdraw from the agreement – and the possibility that other nations might follow suit – has raised concerns about the stability of these commitments.

The United States has had a tumultuous relationship with the Paris Agreement. During his first term in office, Trump withdrew his country from the climate pact in 2017, citing economic concerns. The U.S., under his successor Joe Biden, rejoined it in 2020.

RELATED STORIES

[ Indonesia’s coal-fueled contradiction: Power plants cast shadow on green pledgesOpens in new window ]

This time, the situation is different, Mahawan said.

“Public and congressional support, particularly among Republicans, is stronger now,” he said referring to the U.S. “That means the impact could be even greater than when Trump withdrew the first time.”

For Indonesia, the world’s fourth-most populous country and a major coal exporter, the stakes are particularly high. The nation relies heavily on coal but has pledged to phase out coal-fired power plants in favor of renewable energy.

Jakarta aims to launch its first nuclear power plant by 2032 to diversify energy sources and reduce coal dependence, which generates 67% of its electricity. The planned 500 MW thorium-fueled plant, developed by ThorCon PT Indonesia, is to be constructed on Kelasa island, in the Bangka-Belitung Islands province, at an estimated cost of U.S. $1.05 billion.

Despite the push for nuclear power, critics argue that Indonesia’s vast renewable potential – solar, wind and hydro – remains underutilized, with renewables contributing only 14% to the energy mix, short of the 19.5% target. In addition, safety concerns linked to a nuclear plant are significant, given Indonesia’s seismic activity.

JETP

Any transition requires significant funding, much of which was expected to come from international initiatives such as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), a $20 billion program.

Doubts have emerged about JETP's future as Jakarta media reported that Washington stepped down as co-leader of the program.

Hashim Djojohadikusumo, Indonesia’s presidential envoy for climate and energy, has called JETP a “failed program,” citing a lack of disbursed funds.

“There’s been a lot of talk but no action,” he said at a sustainability forum in Jakarta last week. “The promised $5 billion out of $20 billion has not materialized.”

This funding gap could slow Indonesia’s transition away from coal.

“If the U.S. refuses to comply with the Paris Agreement, why should countries like Indonesia be expected to?” said Hashim, a businessman and brother of Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto.

He said Prabowo had no plans to retire all coal plants by 2040, calling such a move “economic suicide.”

Fabby Tumiwa, executive director of the Institute for Essential Services Reform, disputed Hashim’s claims that JETP had failed.

“JETP funding isn’t a direct cash grant but is distributed through multiple mechanisms, including technical assistance, equity investments and bilateral or multilateral financing,” he told BenarNews.

As of December, he said, donors had disbursed $230 million in grants for 44 projects, with another $97 million pending approval.

US role

The United States historically has been the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, responsible for 527 gigatons of carbon emissions since the 18th century, according to the United Nations Environment Program.

Washington’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement not only weakens global climate efforts but also sets a troubling precedent, said Edvin Aldrian, a climate researcher at Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency.

“The U.S. influences global climate policies. The concern is whether other countries, including Russia, will follow suit,” he told BenarNews. “That would have major consequences for emissions reductions, both in terms of funding and concrete action.”

Meanwhile, Bhima Yudhistira, director of the Center for Economics and Law Studies, said Indonesia should look beyond the U.S. for climate financing.

“Indonesia must seek new partners, such as those in the Middle East,” he said, noting that the United Arab Emirates had already invested in Indonesia’s renewable energy sector, including a floating solar power plant in West Java.

Edvin remains optimistic that Indonesia can meet its climate targets without U.S. assistance.

“We can find new partners,” he said. “Indonesia doesn’t rely solely on the U.S. We have strong ties with China, Japan, and the EU.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to note that Washington has stepped down as co-leader of the Just Energy Transition Partnership.