Malaysia, the Southeast Asian nation with a checkered past where a free press is concerned, jumped 40 spots on the annual World Press Freedom Index of 180 countries released by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) on Wednesday.

Apart from recording the biggest jump in the report that coincided with World Press Freedom Day, Malaysia, at 73, ranked best among nations in the region. Elsewhere, Thailand ranked 106, up from 115; Indonesia ranked 108, up from 117; the Philippines ranked 132, up from 147. Bangladesh, at 163, fell from 162 in 2022.

“The unexpected increase of 40 ranks is positive for the country and the government. What is important is commitment,” Fahmi Fadzil, the communications and digital minister in Malaysia’s five-month-old government, told BenarNews. “And I emphasize the commitment to ensure media freedom and a good atmosphere for journalists.”

The authors of the RSF report noted that the induction of a new coalition government in Malaysia had contributed to its leap on the press freedom index.

The Washington Post introduced the 2023 edition of the index during a 90-minute online program which featured a live interview with U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

“Journalists around the world are increasingly under siege,” Blinken said.

“We’re actually trying to put tools in the hands of journalists and independent media so that they can push back, so that they can sustain what they’re doing.”

In a statement issued separately by his agency, Blinken said, “Imprisonment is not the only threat reporters face. Journalists covering violent conflict and corruption are subjected to intimidation and abduction, often perpetrated with impunity.

“Elsewhere, journalists face discrimination, censorship, and weaponized justice systems. Governments around the world have used various tools of repression to force media outlets to close.”

Earlier, Clayton Weimers, RSF’s U.S. executive editor, discussed efforts by journalists to do their jobs in the face of danger.

“2022 was an especially dangerous year,” Weimers said – at least 57 members of the media were killed and 533 were detained last year.

He noted that authoritarian governments were stepping over the media to get their messages out.

“Every day we are seeing new examples of how authoritarian regimes can use emerging technology,” he said. “Just muddying the waters is often enough.”

Reporters Without Borders noted that this was the second index compiled using methodology devised in 2021 by a panel of experts from the academic and media world. The methodology is based on a definition of press freedom as “the ability of journalists as individuals and collectives to select, produce and disseminate news in the public interest independent of political, economic, legal, and social interference and in the absence of threats to their physical and mental safety.”

The index is based on five indicators – political context, legal framework, economic context, sociocultural context and safety.

Malaysia

Malaysia’s score of 62.83 – the average of the five indexes – increased by more than 11 points from 2022 – leading to the 40-spot jump in the rankings.

The report noted that Malaysian journalists are rarely the target of physical attacks, but can face “judicial harassment and smear campaigns.”

“Recent threats to journalism have included prosecutions forcing the victims to incur huge legal expenses, police searches of media outlets, violations of the confidentiality of journalists’ sources and expulsions of foreign reporters or whistleblowers,” it said.

In Kuala Lumpur, Farah Marshita Abdul Patah, president of the National Union of Journalists of Malaysia, said the government was more open to “media practitioners.” In the past, she said, the government had worked with “official media.”

“In terms of fair reporting, in my opinion, it depends on the topic involved,” Farah Marshita told BenarNews, adding that “in political affairs, to be objective without prejudice is difficult as media companies usually owned by government bodies have their own affiliation and direction.

“However, in terms of crime, court coverage, it is not an issue.”

Philippines

Malaysia’s neighbor, the Philippines, ranked 132 of 180 countries – up 15 spots from 2022.

RSF said that while the 1987 Constitution guarantees freedom of the press, the law does not protect journalists. It noted that Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa could face years in prison if her appeal of a defamation conviction fails.

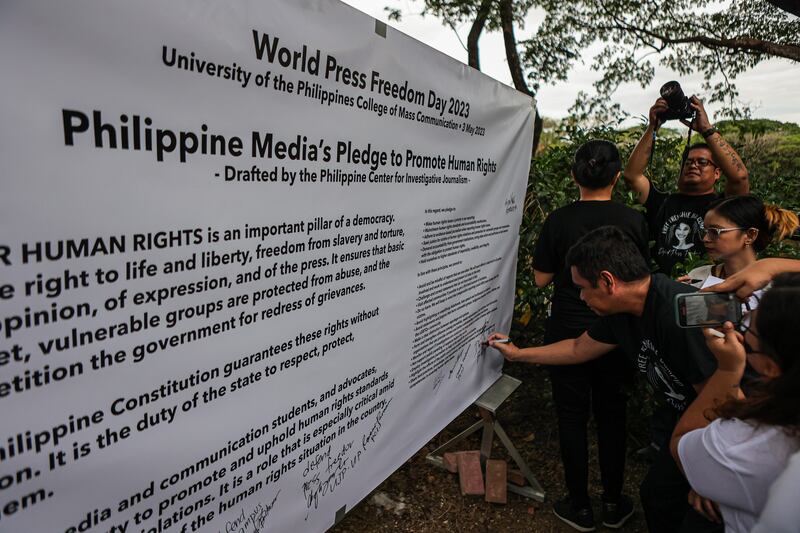

On Wednesday, the Foreign Correspondents Association of the Philippines (FOCAP) and the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), rallied their members to continue reporting fearlessly despite a hostile climate and threats.

At least two reporters have been killed since President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the namesake son of a late Philippine dictator, took office last year. Percy Lapid, was fatally shot near his home in Metro Manila by gunmen allegedly hired by the country’s ex-prisons chief. Since 1986, nearly 200 journalists have been killed in the Philippines, based on the data and monitoring of the NUJP.

“FOCAP calls on the government, public officials, executives and other people in power to respect and uphold the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of the press and its vital role in a functioning democracy,” the group said in a statement.

Before leaving for Washington this week, President Marcos vowed to work “hand-in-hand” with the media to strengthen press freedom, noting his administration’s commitment to protecting journalists and their rights in the practice of their profession.

“This government will remain committed to ensuring transparency and good governance, freedom of expression and of the press, and the protection of media practitioners and their rights in the practice of their profession,” he said.

Indonesia

The report noted that in Indonesia, journalists can be jailed for up to six years for online defamation or hate speech, “although these offenses are not clearly defined.”

“The adoption of a new Penal Code in December 2022 poses new threats to the free exercise of journalism, with several provisions relating to blasphemy and articles meant to fight against ‘fake news’ that, as they stand, seriously jeopardize investigative journalism,” it said.

RSF ranked Indonesia 108, up nine from 117 in 2022. Media organization AJI Indonesia called for the government to protect freedom of speech and the press.

Meanwhile, the communication and information deputy minister noted that President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo emphasized the importance of World Press Freedom Day.

“So we appreciate it because we can say that press freedom in Indonesia is improving. The government is no longer interfering with the press,” Usman Kansong told BenarNews.

Thailand and Bangladesh

Thailand, which has been ruled for nine years by a government with deep ties to the military, ranked 106, compared to 115 in 2022.

RSF noted that journalists must know that the judicial system cracks down on criticism of the government or the monarchy. Those convicted of violating the strict anti-royal defamation law Lèse-Majesté face mistreatment in prison.

Bangladesh, in South Asia, saw its ranking fall one spot to 163 – the lowest in the region.

RSF called the Digital Security Act one of the world’s most draconian.

It permits searches and arrests without any form of warrant, violation of the confidentiality of journalists’ sources for arbitrary reasons and a sentence of up to 14 years in prison for any journalist who posts content deemed to be “negative propaganda against (...) the Father of the Nation,” namely the current prime minister’s father.

The Center for Governance Studies, a private think-tank in Dhaka, has been researching 1,295 Digital Security cases filed since October 2018 – noting that 355, or more than 27%, of those accused were identified as journalists.

In Dhaka, Law Minister Anisul Huq said, “I want to say clearly that the Digital Security Act will not be repealed under any circumstances, but some amendments can be made if necessary.”

Iftekharuzzaman, executive director of Transparency International Bangladesh, expressed disappointment about another bad score.

“Bangladesh is responsible for this embarrassing situation due to various oppressive laws including the Digital Security Act and their arbitrary use. There is no option to abolish these laws,” he said.

Bangladesh journalists, however, were able to mark some good news on Wednesday as Matiur Rahman, editor of leading daily Prothom Alo, was released on bail on charges related to the security act.

Ili Shazwani and Iman Muttaqin Yusof in Kuala Lumpur, Froilan Gallardo, Mark Navales and Richel V. Umel in Cagayan de Oro, Philippines, Ahammad Foyez in Dhaka and Pizaro Gozali Idrus and Nazarudin Latif in Jakarta contributed to this report.