When Malaysia last week named a 69-year-old Filipino man a terrorist for his alleged link to a 2013 attack on the country, observers initially wondered about the 10-year wait.

Turns out that naming Muhammad Fuad Abdullah Kiram a terrorist wasn’t entirely about that decade-old attack in Sabah state after all, a Malaysian official acknowledged publicly.

It was about going “on the offensive” against a group of eight people claiming to be heirs of the erstwhile Sultan of Sulu, who are eyeing a hefty chunk – nearly U.S. $15 billion – of Malaysia’s assets to settle a colonial-era land deal.

The former Sultanate of Sulu was a small archipelago in the southern Philippines, part of which is now in Malaysia, in oil-rich Sabah.

Fuad Kiram is one of the members of the group that last year won a $14.92 billion arbitration award against Malaysia from a French court, on the basis that the Southeast Asian nation had in 2013 stopped making annual payments to the purported Sulu heirs under the 19th century deal.

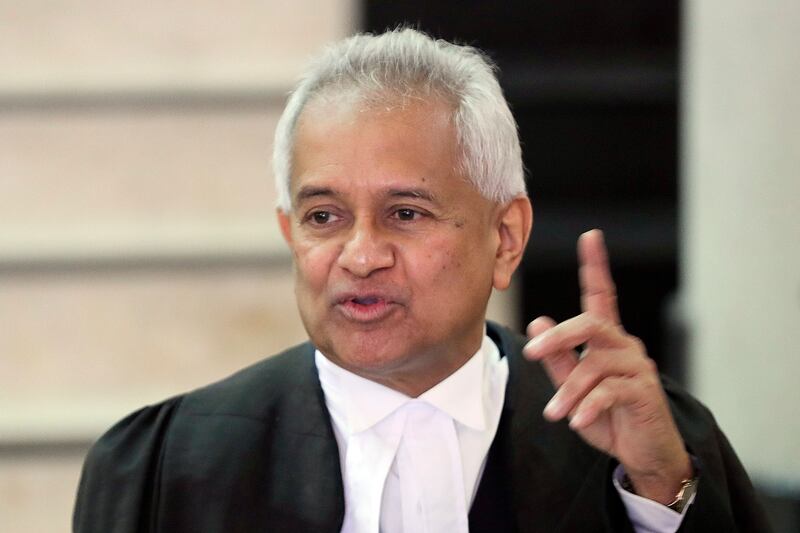

Paul Cohen, the lead counsel representing the purported heirs of the former Sulu Sultanate in their arbitration, said Malaysia was running out of options, and that is why it resorted to naming Fuad Kiram a terrorist on April 11.

“Of course, Fuad Kiram is no terrorist. And of course, Malaysia knows this. They just made this up in desperation because every other trick is failing,” Cohen told BenarNews.

At a media briefing April 11, reporters asked Khairul Dzaimee Daud, an official in the Legal Affairs Division of the Prime Minister’s Department, why it took the government 10 years to name the Filipino a terrorist. He said legal procedures needed to be followed before such a classification could be made.

Others have raised questions about why only Fuad Kiram was named a terrorist and not others from the group of eight who could also be part of the Royal Sulu Force that carried out the 2013 attack.

BenarNews contacted the Home Ministry for more details but did not hear back.

What Malaysia has said is that the government has spent $7 million on the legal dispute, including costs for international legal representatives, translations, historical research and related issues. It has also set up an informational website, which presents the government's side of the case in five languages.

Additionally, a group led by Law Minister Azalina Othman Said plans a visit to France, Spain, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, where the arbitration case has done the rounds, to inform the courts there about Malaysia’s stand.

Why was Malaysia paying former Sultanate heirs?

Back in 1878, for reasons unknown, the then-Sultan of Sulu made an agreement with two men who were representatives of the British North Borneo Company, to cede sovereignty to a significant portion of North Borneo, now known as Sabah and part of Malaysia.

In return, the company would pay “cession money” of 5,000 silver dollars a year, which was the currency of the time, to the sultan, and his successors forever.

Additionally, in 1903, the Sulu sultan ceded some more islands to the British North Borneo government for $300. When the British government became the successor to the British North Borneo Company, the former started to pay the annual sum of $5,300 to the Sulu heirs.

When Malaysia gained freedom from the British, that was a chance to become free from this payment, former Attorney General Tommy Thomas noted last year in an article for a local media outlet.

“Our founding fathers could have easily argued that the 1878 grant was a colonial relic which did not bind the new federation, and the annual obligation to pay compensation shall remain with the British,” Thomas wrote in The Edge Markets in July 2022.

“Regrettably, the new federation instead assumed the legal obligation of the retreating British colonial power to pay annual compensation without hesitation or protest. Malaysia made such payments annually and without interruption until 2013.”

During those years, Malaysia paid an annual amount of 5,300 ringgit (currently $1,236) to the representatives of the purported Sulu heirs living in Jolo island in the Philippines, according to Malaysian historian Shari Jeffri.

North Borneo History Research Center head Shari said there has been confusion on what the currency was back then. Shari said the dollar back then was the Malayan dollar, which changed to the ringgit.

“The amount remains the same although the term used to refer to the currency has been changed,” Shari told BenarNews.

Why did Malaysia stop payments to Sulu heirs?

On Feb. 11, 2013, a group of 200-odd armed members of the so-called Royal Sulu Force entered Sabah’s Lahad Datu district from the Philippines in an attempt to take over the state.

The 2013 invasion led to a standoff with Malaysian security officials that lasted more than six weeks, according to a 2016 paper by authors Jasmine Jawhar and Kennimrod Sariburaja for The Southeast Asia Regional Center for Counter-Terrorism.

Ten Malaysian security personnel, six civilians and 68 members of the so-called RSF were killed in the fighting.

The invaders made three demands, wrote Jawhar and Sariburaja.

“Firstly, Malaysia must recognize the Sulu Sultanate. Secondly, Malaysia must acknowledge that a part of Sabah belongs to the Sultanate and thirdly, the group demanded that Malaysia pay a sum of $7.5 billion as compensation to the group, given that Malaysia, in their view, had been occupying Sabah since 1963,” the authors said.

The militants were led by Raja Muda Agbimuddin Kiram, the brother of the self-proclaimed Sultan of Sulu, Jamalul Kiram III, the authors said.

Malaysia did not entertain any of these demands, and labeled the invaders terrorists. Then-Prime Minister Najb Razak’s administration also stopped payment of the annual amount of $1,236 that successive governments had been paying since 1963 to the Sulu heirs.

Although Najib’s government did not officially state that the invasion was the reason the payments stopped, he has often asked on his Facebook page why the Sulu heirs should be paid after what they did in 2013.

The purported heirs have denied any involvement in the incursion, and the group involved in the arbitration has condemned the attack, Reuters news agency reported.

Taking Malaysia to court

Four years after Malaysia stopped annual payments to the Sulu heirs, a group of people claiming to be descendants of the erstwhile sultan, decided to begin arbitration in a European court with the financial backing of a British global litigation fund called Therium Capital Management Ltd.

The legal action they sought to pursue would be based on the 1878 deal and would claim Malaysia violated the deal by non-payment since 2013.

Courts in the U.K. and then in Spain rejected the purported Sulu heirs’ arbitration attempts against Malaysia, after which the case made its way to France, ending up in a Paris arbitration court.

In February last year, the Paris court ordered Malaysia to pay nearly $15 billion to the litigants, as compensation for failed payments since 2013. The amount included valuation of the land in Sabah and its natural resources such as oil and gas.

But the original deal, Malaysia’s former Attorney General Thomas argued, stipulated that disputes were to be settled by “Her Britannic Majesty’s Consular-General for Borneo,” which no longer exists, but its place has been taken by the Sabah courts.

Malaysia, therefore, said it did not recognize the ruling, which it called illegal. Subsequently, last July, the Paris Court of Appeal issued a stay on that arbitration ruling because its enforcement could infringe on Malaysian sovereignty.

The self-proclaimed Sulu heirs contested the suspension but the court upheld the stay in March.

‘Dangerous precedent’

Despite last July’s suspension of the nearly $15 billion award, Malaysian state oil firm Petronas in February confirmed that it received seizure orders on two of its units in Luxembourg, as the so-called Sulu heirs attempted to enforce the award.

According to Reuters, although the ruling was suspended in France, it remains enforceable overseas under a United Nations arbitration treaty.

Petronas said back then that it would continue to defend its position. BenarNews contacted the company to get the latest information on the seizure but did not hear back.

Malaysia’s Law Minister Azalina said that new Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim's government would vigorously dispute the arbitration, as the claim lacks legal basis and sovereignty cannot be decided by a commercial arbitrator.

“The idea that a commercial arbitrator could challenge our sovereignty is unacceptable. Be assured that our government will contest these claims,” she said last month in the Parliament.

The Philippines, meanwhile, last August sought to distance itself from the case, saying it was "in the nature of a private claim" between two private parties and does not involve Manila.

Oh Ei Sun, a senior fellow at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, told BenarNews that the case could set a harmful example.

“International law is experiencing a trend where the clear distinction between public and private international law is being intentionally blurred, making it easier for non-state entities to bring states to court or arbitration tribunals, and enforce judgments or awards against them,” he said.

“If this case favors the Sulu side, it would set a dangerous precedent in international law that would erode further the sovereignty or legal immunity of states.”