Data shows that commercial ships are avoiding areas in the South China Sea that have been developed and militarized by China, while experts say that Beijing’s bases and naval build-up are ultimately meant to secure China’s trade routes through the disputed maritime region.

China conducted large-scale military exercises in the Paracel Islands in July and August, amid rising tensions with the United States. In both cases, it halted all maritime traffic through the area for the exercises’ duration; in the second set of drills, it launched anti-ship ballistic missiles into the water.

On Saturday, it announced two smaller-scale exercises in the Paracels for this week – bringing the total count of drills conducted in the area to four.

Experts said the South China Sea drills, which encompassed an area of over 13,000 square miles off China’s Hainan province, may have disrupted shipping, but just for a few days.

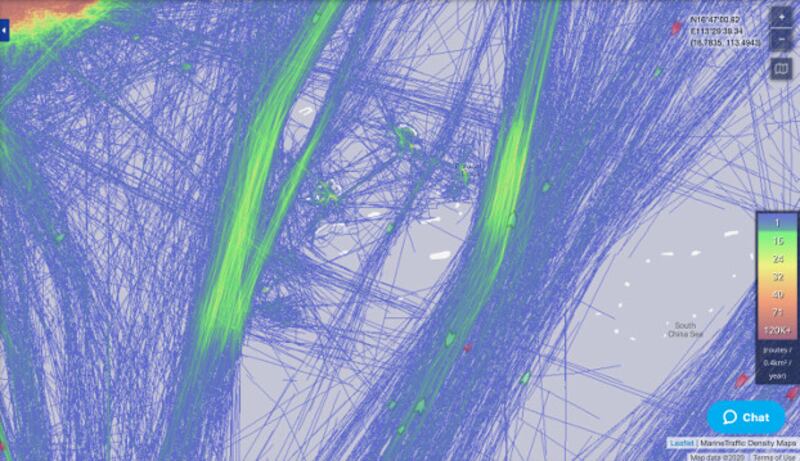

More significant are trends revealed by ship-tracking data covering a longer period that show commercial ships avoiding China’s outposts and artificial islands in the Paracels in the northern part of the South China Sea, and particularly in the Spratly Islands further south.

In both locations, shipping traffic is becoming more concentrated on a small number of increasingly busy routes.

“There’s only a series of very narrow passages through the South China Sea straddling the Spratlys. It doesn’t take much to cause a disruption in the supply chain, over those sea lanes,” said Sal Mercogliano, a maritime historian at Campbell University in North Carolina.

“I think one of the things the Chinese are trying to do is ensure that those commercial routes stay open, and that’s one of the reasons they’re putting themselves on those routes, to ensure there is not an interdiction. There is not a stop to the flow of goods and material,” he said.

But if that’s the goal – a trading environment on China’s terms – it deviates sharply from how the United States and key allies view the problem.

The U.S. has often argued that China’s militarization threatens free trade and unobstructed shipping traffic. Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, India, and Germany have echoed this concern.

Nearly one-third of the world’s trade passes through the South China Sea, constituting goods valued at roughly $5 trillion. Out of the top 10 ports handling the cargo ships that ferry these goods, nine are in Asia.

China claims virtually all the South China Sea on the basis of “historic rights,” a position unsupported by international law. That has put Beijing at odds with six other Asian governments – Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

China has asserted its supposed jurisdiction through deployments of its coast guard and navy, both of which constitute the largest fleets of their kind in the world, according to the annual China Military Power Report put out by the U.S. Department of Defense.

So far, there is little evidence of serious disruption of commercial shipping in the South China Sea. However, data gathered by MarineTraffic, an online service that tracks ships, shows that in 2017, most ships carrying oil or cargo were going around the Paracels, although a more direct route through the Paracels would decrease fuel costs.

Shipmap, a shipping visualization tool developed by the University College London’s Energy Institute, shows that in 2012, container ships would more frequently cut through the Paracels, passing between Lincoln Island and Woody Island. This was before reclamation and sand dredging projects turned Woody and Lincoln islands into Chinese military outposts in 2014.

The U.S. Navy performed what it called a freedom of navigation operation through the Paracels in late August and framed that as an effort “to ensure critical shipping lanes in the area remain free and open.” The Paracels are wholly occupied by China, but they are also claimed by Vietnam and Taiwan.

Mercogliano and Johan Gott, a partner at the political risk advisory and consulting firm PRISM, said the impact of ships not cutting through the Paracels remains relatively minor.

Farther south, MarineTraffic data from 2017 shows ship traffic avoiding the disputed Spratly islands almost entirely. A single narrow lane off Palawan, in the Philippines, is the main route through the waters there.

Previous maps of the area, including one from 2012, suggest this isn’t a recent phenomenon. Due to its perilous waters, shipping has long given the area a wide berth.

But experts say a desire to maintain Chinese access to these narrow and congested sea lanes has motivated China’s spree of island building in the Spratlys, where conflicting territorial claims are particularly complex.

China has bases at Fiery Cross Reef, Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, Cuarteron Reef, Johnson South Reef, and Gaven Reef that include runways and harbors to accommodate coast guard or civilian ships. Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam all either occupy or claim assorted islets, reefs and shoals in the island chain.

A close-up of the Spratly Islands and the routes commercial ships take to avoid the area. Because of the few narrow passages through the area, Mercogliano believes it would take little effort to disrupt crucial shipping lanes there, which explains China’s military build-up in the area.Data courtesy MarineTraffic.

‘Who’s the better sea power?’

Gott noted that it was not in China’s interest to interfere in commercial shipping as China’s goods sail through the area as well. Seven of the 10 largest commercial ports are in China, and some of the biggest shipping companies in the world are Chinese and dependent on access to the waterway.

“In peacetime, I don’t see there being significant disruption to the flow of goods,” Gott said.

He said military exercises like the ones conducted this summer in the Paracels by China would have little impact on shipping companies’ costs and profit as ships are accustomed to adapting to circumstance.

“There is a disruption to shipping, but it is a limited amount of time, and I think shipping companies are sort of used to having to reroute and renavigate, because of weather, because of military [exercises], whatever it may be,” Gott said. “I don’t think that’s going to be a noticeable difference in terms of your cost of shipping one container.”

China asserts it has sovereignty over disputed areas in the South China Sea, and on Monday described its construction of military facilities in the Spratlys as an exercise of its rights to “self-preservation and self-defense under international law.”

“China’s construction on our own territory is aimed to meet the civilian need in the South China Sea, provide more public goods and services to the region and beyond, and fulfill our international responsibilities and obligations,” Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin told a news conference in Beijing, according to a transcript posted by the ministry.

“Deployment of necessary defense facilities on the Nansha Islands is an exercise of China's right to self-preservation and self-defense under international law,” he said, referring to the name China uses for the Spratlys.

Those comments point to what Mercogliano identifies as the primary reason for China’s militarization of the region – its desire to secure its own trade out of concern that the U.S. or any other country could interrupt it.

Also, at a time when many other countries have abandoned the idea of having a national merchant fleet, China has embraced it, Mercogliano said.

China has a vastly bigger merchant marine than the United States or other countries, designed to ensure Chinese shipping continues in times of crisis. China also builds 40 percent of the world’s cargo ships.

“Who’s the better sea power?” Mercogliano posited. “If you’re in a shooting war, the U.S. Navy is, but if you’re in peacetime, with the commercial aspect, it sounds like China’s in the better position.”

China is also positioning itself as the main guarantor of security and law enforcement in the South China Sea, and recently performed its first ever interdiction of a suspected drug-smuggling ship in the Spratly Islands, nearby its military base at Fiery Cross Reef.

China's legislature recently adopted a new law on maritime traffic that grants maritime police agencies such as its coast guard the right to pursue and apprehend any suspect ship moving through its "jurisdictional waters," a vague term that includes maritime territory claimed in the South China Sea.

“They want to be the regulatory agency. They don’t want to leave a void out there for the U.S. or other nations to have to fill. They’d rather fill it themselves,” Mercogliano said.