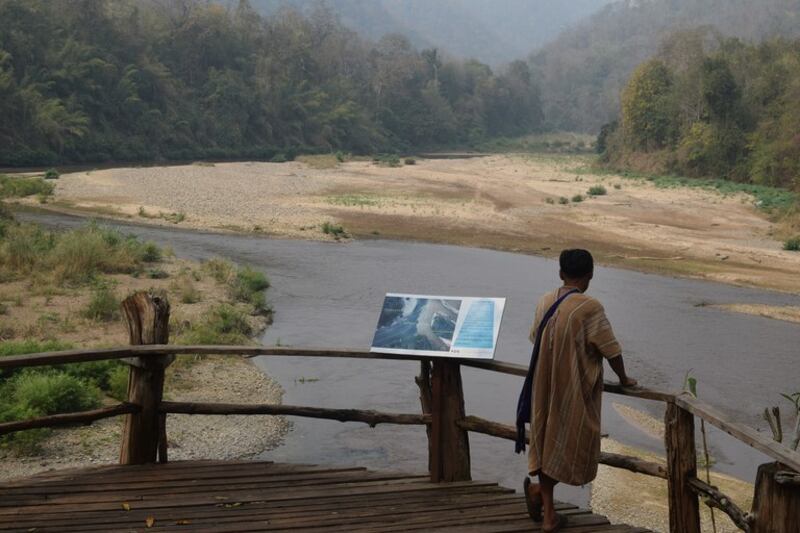

For a full year, Singkarn Ruenhom will be working with 14 others to document the potential destruction that a huge dam could wreak on the residents and rural farmland along the Yuam River.

They will be conducting a “people’s environmental impact assessment” to counter the findings of a 2021 study by Thailand’s Royal Irrigation Department and Naresuan University that reported only four houses in the river village of Mae Ngao, where 170 people live, will be affected by new infrastructure.

Local residents say the destruction from the dam – officially called the Yuam River Diversion Project – will be far greater, clearing a minimum of 600 hectares of land and affecting the livelihoods of an estimated 40,000 people in 46 villages.

“I think about life in the water, the plants and the animals. They will go extinct.” If the project goes through, Singkarn said after hooking a fish in the river, taking a photo and documenting his catch in Thai and Karen. “That’s something we can’t bring back.”

In the past, such grassroots research efforts have warranted some big wins for communities in both Thailand and Myanmar over major construction projects that were scratched. In those cases, too, environmental impact assessments were either bypassed altogether or not made public.

In 2019, villagers in northeast Thailand staged forums and protests alongside their environmental study, which successfully blocked the company from moving mining equipment to a new potash drilling site despite obstruction lawsuits hedged from the company.

The Hatgyi Dam, a project which was slated for construction in a conflict zone in Karen State, was delayed due to both ongoing conflict and grassroots impact reporting. After the coup in 2021 in Myamar, it also faced attempted revival under military administration.

Saw Tha Poe, who works at Karen Rivers Watch, says the cross-border community has needed to join forces to demonstrate the impact to areas downstream and track fish species.

“Many Karen people along the river in both the Thai and Burma side have a good relationship and collaborate together, doing the research, doing the surveys, for example, about the fish species,” he said, adding that the community has found some to be endangered.

Grassroots research

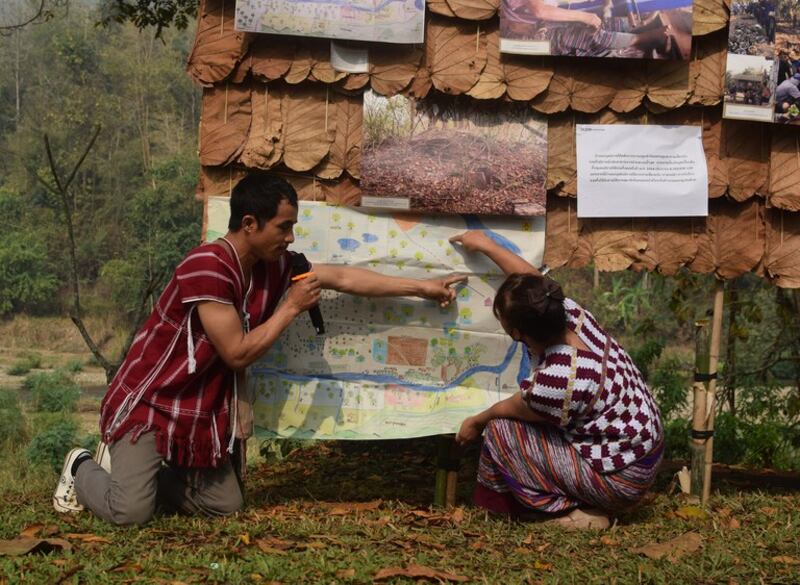

With a group of volunteers, Thai professors Malee Sitthikriengkrai and Chayan Vaddhanaphuti teach research methods they can use alongside their daily routines to document how the soon-to-be dammed river would affect not only livelihoods but the local environment overall.

Chayan has been fine-tuning this research since the 1990s, and it has since become popular around Southeast Asia. For the Karen, Chayan says, this research is particularly useful in giving indigenous people a voice.

Roughly 80 percent of Mae Ngao residents are Karen, many of whose families have resided in Thailand for over 60 years. A few have more recently come across the border from Myanmar, where their ethnic group has been engaged in a war with the military for decades.

Despite residing in Thailand for decades, Singkarn says as many as half of the Karen residents in the village are still applying for their Thai identification card – a process that can take as long as 20 years.

And non-Thai citizens are not legally entitled to full compensation for their land or livelihood. Additionally, any land designated part of the newly finished Mae Ngao National Park under the National Park Act could mean a long legal battle, or no compensation at all.

“People who have the color card, they can’t travel out of the district. If their houses have been flooded, where are they going to live?” Singkarn asked. Color cards refer to pink or white cards that allow migrants to work in Thailand or show they’re in the process of proving their citizenship.

“Where are they going to work to make money, because they have been locked in this district? They [will] have no other place to go because of the water.”

But when inspectors came to measure the impact of the dam on the surrounding area, they minimized the damage, said Jor Da, one of Mae Ngao’s Thai-Karen residents.

“If it happens, it will be challenging for the families here,” he said. “During the meeting [with residents] they only showed as little damage as possible. We live here inter-depending with trees and forests.”

Upon the publication of the 2021 environmental impact study, Malee said the original report’s thousands of pages about impacted areas were almost entirely inaccessible to villagers.

After being charged over 20,500 Thai baht (U.S. $600) for printing the report, they received a copy that was heavily redacted and grossly underestimated the harmful effects of the project.

Neither Naresuan University nor the Royal Irrigation Department responded to request for comment from Radio Free Asia (RFA), a news site affiliated with BenarNews.

“It’s very difficult for the community to raise their voice,” said Sor Rattanamanee, whose Community Resource Centre Foundation is providing legal counsel to Mae Ngao and helped them obtain the original impact assessment.

“Some of them may not have the identity card, that’s why it’s very difficult for them to complain because the officers will use this opportunity to put pressure on them and [put] them at risk.”

Layers of impact

While Mae Ngao’s full report won’t be published until later this year, graduate student Manapee Khongrakchang says findings already point to major disruptions for the border community.

The fishermen found that nearly all 53 species of fish documented in the river so far would be impacted by the project by changes in food chain and typology of the river.

The village is also documenting its relationship to the river and history through art and storytelling, calculating total revenue from cash crops year-round, and documenting unique species found in the area.

"We have one species that's going to be extinct for the Yuam and the Ngao River that's called pla sa nge [short-finned eel]," Manapee said.

Villagers also raise concerns about a species of clam, which lives in the rocky bottom of the river and would be impacted when other types of sediment flood the region. Both are sources of food for the community.

“It’s questionable to me – is that fair for one species, that they can’t get back to the river that they live?” she said.

On a nearby hill, Daw Po lives in one of the only houses in Mae Ngao documented in the original environmental impact assessment.

Despite being one of the few certain of compensation and legally living in Thailand, she has little faith in this outcome. Her house sits next to the spot designated to be the site of six water-pumping stations to pump into an eight-meter pipe carrying water 600 meters below ground.

“[Here], I will not brood over the house if I need to run. If I own something, I will be sorry to lose it. I am not sure whether I should go or stay,” Daw Po told RFA.

While she and her elderly parents cannot attend meetings in the village anymore due to health issues, she’s concerned about maintaining access to natural foods from in and around the river.

Despite past successes, Malee says it will take more than just research to stop the mega-projects from developing remote communities with little chance of fighting back. After the research is finished, they plan to hold meetings to share their findings with the public.

“The government is like a superpower compared with us. We are like ants and they are like elephants,” she said.

“The government and the irrigation department thought, ‘Oh, for this village, no one will pay attention,’ or they can build up this project easily. But it won’t be that way.”