Only a few months into office, Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin is trying to revive a plan for a land bridge that would give international shippers a shortcut between the Pacific and Indian oceans without having to pass through the Malacca Strait at Singapore.

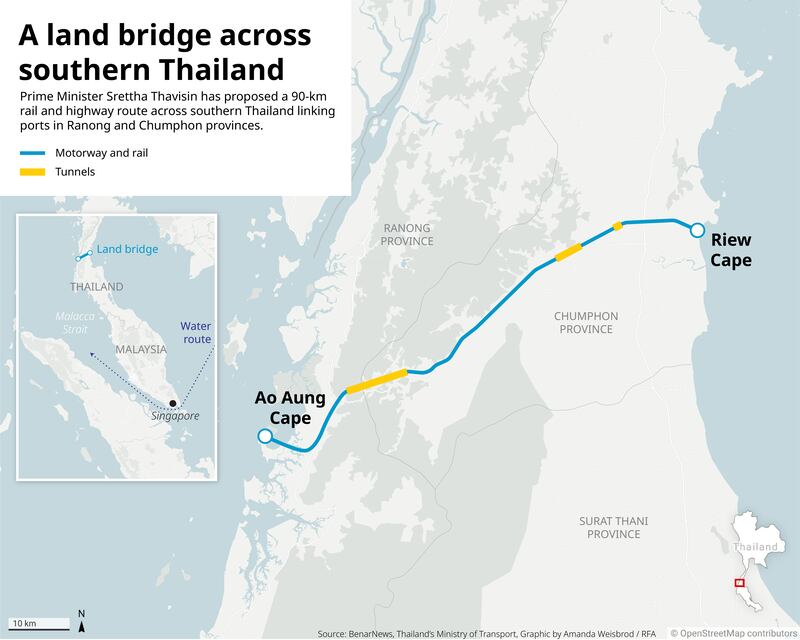

The land bridge concept would cut across the Kra Isthmus in southern Thailand and join the Gulf of Thailand to the Andaman Sea, through the construction of a rail line and highway.

The prime minister, a real estate tycoon before entering politics recently, has been selling his plan lately on both sides of the Pacific.

In San Francisco last month, Srettha addressed potential investors on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit. There, he pitched the estimated 1 trillion baht (U.S. $28.5 billion) megaproject as a way to cut shipping costs and transportation time by up to two or three days.

In mid-October, on the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, China Harbor Engineering Co., a Chinese state-run infrastructure developer, expressed interest after a meeting with Srettha, according to international media.

Other potential investors from the United States, China and the Middle East have also expressed interest in the project, Thai government spokesman Chai Watcharong said.

Srettha expressed hope that the project could be launched to replace an old concept of building a canal across the Kra Isthmus to join the two seas. In recent decades, the canal idea broke down over disputes about its viability – both economic and logistic – as well as concerns about its effects on national security.

Outlines for the international bidding process have been laid out. A consortium of investors would bid for a 50-year contract to develop a land bridge in the south of Thailand linking seaports on both sides of the southern isthmus through a 90-km (56-mile) motorway and rail connecting ports in Ranong and Chumphon provinces.

The government plans to conduct international presentations to promote the project before receiving bidding in 2025 with construction expected to begin later that year before its opening in 2030.

“We also have plans to hold a roadshow in Japan in the near future, and we might return to China for a proper roadshow later on,” Chai told BenarNews.

He said that the land bridge megaproject should be attractive to investors with port management skills from countries including Singapore, for example, as they can build on their experience and capital with their investment in Thailand.

“There are fringe benefits to the project. Investors can develop lands around the project,” Chai said.

“There will be more manufacturers to relocate to Thailand, which is located in a suitable location where goods can be shipped around the world. Investors have to come up with a proposed logistics system to manage the ports.

“Thailand can offer the location and the opportunity. This is a total package.”

Old idea, new era

The land bridge is sometimes viewed as a revision of the Kra Canal project, a strategic initiative dating back centuries.

In the same way that the bridge would link the two oceans, the canal would provide a shortcut between the Pacific and Indian oceans, bypassing the choke point in the Strait of Malacca off Singapore.

Since at least the 17th century during the Ayutthaya period, the Siamese capital that flourished in the central part of modern-day Thailand during the 14th to 18th centuries, canal projects to increase commerce in the south have been raised.

“This idea has been around in one form or another for around 300 years, either a canal or a rail-road link. It resurfaces every time the Thai economy is on the skids because governments see it as a way to create jobs, attract investment and generate revenue,” said Ian Storey, senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore.

Critics pointed to potential flaws in touting the project as a rival to the Strait of Malacca.

Piti Srisangnam, an associate professor of economics at Bangkok’s Chulalongkorn University, said a land bridge would require ships to offload cargo at one sea port to have their products transported by trucks or trains to the other side before being loaded on another ship. This would add time to the trip rather than reduce it.

“When we compare the land bridge idea to what is already in use, which is the Strait of Malacca, it doesn’t constitute an economic viability,” he said. “Because the reduced time spent, said to be at two days, would be too insignificant to persuade a diversion from the Strait of Malacca.”

Instead, Piti said, the projected reduced time could be lost waiting to unload and load ships because of logjams at both ports.

Piti said the government could reframe the project as a bridge of opportunities for goods and services to flow in and out of mainland Southeast Asia and China instead of a replacement for the Strait of Malacca, adding that the Kra Canal idea should be scrapped.

“Thailand has been obsessed with the Kra Canal idea for so long. It never really drops the idea and says it is not going to be done,” he said.

Chai, the government spokesman, said the ports would be operated under a single command system, which could reduce logjams and cut logistics cost by 15%, along with four days from the trip time compared to ships passing through the Strait of Malacca.

Storey, meanwhile, is not convinced the land bridge will attract international investors.

“China never considered a Kra Isthmus infrastructure project as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, U.S companies simply aren’t interested. Even Thai companies know it’s not feasible, but play along to keep the government happy,” he said.

“I have little doubt the Thais will still be talking about a Kra Canal or land bridge 300 years from now.”