Although three-quarters of migrants surveyed in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand said they suffered some type of abuse while leaving their homelands via people-smuggling networks, nearly half said they would do it again, the United Nations said in a report released Tuesday.

The U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime conducted a survey of nearly 4,800 migrants and refugees in those three countries who had turned to illegal networks to smuggle them into Southeast Asia, the UNODC’s regional office in Bangkok said in its report.

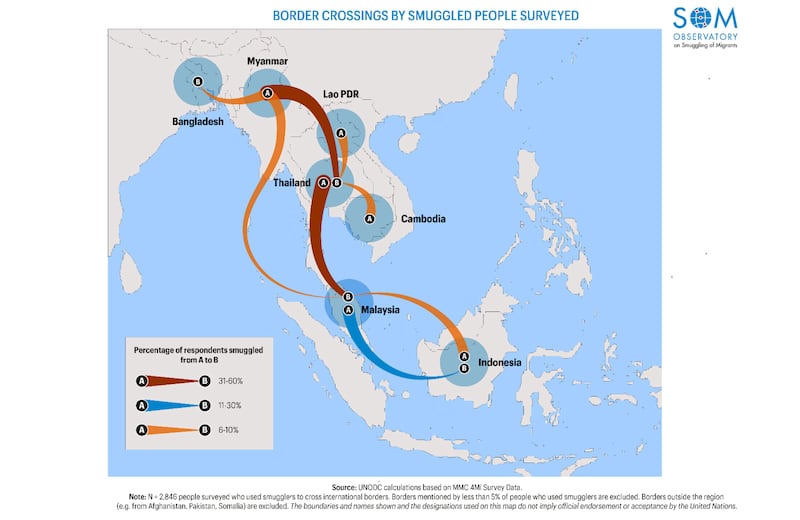

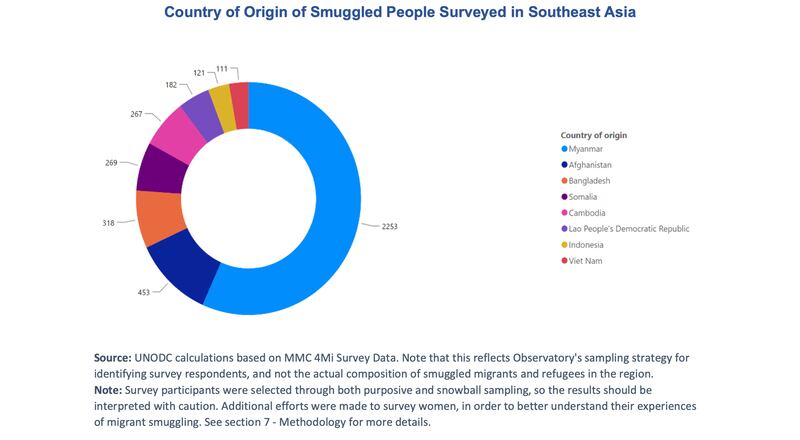

The respondents were abused by the “military, police, smugglers, border guards or criminal gangs,” according to the report titled “Migrant Smuggling in Southeast Asia.” Those who took part in the survey were from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, Somalia and Vietnam, and included Rohingya.

“Migrant smuggling is often not a free or voluntary choice, but an act of desperation, to seek security, safety or opportunity, or freedom from threat of harm, oppression or corruption,” said Masood Karimipour, UNODC regional representative in Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

“The data shows that smugglers may be individual actors, loosely connected criminals, or organized groups. Bringing them to justice is an important part of protecting the people seeking safety and a better life,” he said in a statement that accompanied the report’s release.

The report found that military and police were seen as likely to carry out physical violence; ask for bribes or engage in extortion; cause death; and commit sexual violence during the journey.

“Non-physical violence (e.g., harassment) is more common for men (18% of smuggled men surveyed) than women (13%). Eleven percent of women and 6% of men experienced sexual violence, while 9% of men and 6% of women witnessed death,” the report said.

About one-quarter of the respondents said that climate issues including floods, drought or extreme temperatures drove them to seek out smugglers.

“Climate issues are particularly relevant for smuggled Bangladeshis; three out of four Bangladeshis surveyed said that climate-related or natural environment issues influenced their decision to leave,” the UNODC said.

A similar number said they were pulled into having to bribe officials, or give them gifts or perform favors during their travels.

“[P]eople think that they need smugglers to help them deal with corrupt authorities,” the report said.

Despite this, “Among smuggled people surveyed, almost half (48%) stated that they would have taken the journey anyway, knowing what they did now about the conditions, 40% said that they would not have and 12% were undecided,” the report said.

It found that more than two out of every three respondents said they, family or friends had initiated contact with smugglers through social media, by phone or in person. They pay fees averaging U.S. $2,380.

Nearly 90% of Rohingya – members of a persecuted and stateless Muslim minority group from Myanmar – told interviewers that they used smugglers to get to Malaysia, Thailand or Indonesia.

In light of the report released by UNODC, BenarNews reached out and interviewed three Rohingya who had relied on people-smuggling networks in their efforts to migrate to countries in Southeast Asia other than Myanmar.

One of the three, Shobbir Hussain, 18, is among 2,000 Rohingya who have been sheltering in Indonesia’s Aceh region since October 2023.

Along with about 130 other Rohingya, he arrived in Aceh Besar regency on Dec. 10, from the Cox’s Bazar refugee camp in Bangladesh, after weeks adrift at sea.

Shobbir said his parents sent him on his journey to have a better life.

“Life in the Cox’s Bazar refugee camp, Bangladesh, is no longer safe. There are frequent acts of violence, kidnapping and extortion,” Shobbir said.

“It turns out here is not what I expected either,” he said.

Four months after arriving in Aceh, Shobbir said his life is much like it was in the Bangladesh camp – his time is spent eating and sleeping.

“There is nothing to do, even though I want to go to school or work.”

Shobbir said his father paid smugglers to take him by a wooden boat across the rough Andaman Sea – a 45-day journey to Indonesia – after they promised a better life in Indonesia or Malaysia. He said he did not know how much his father had paid for him to leave.

His father, mother and seven siblings lived in a cramped Cox’s Bazar refugee camp after they were forced to leave Rakhine state following a brutal offensive launched by the Myanmar military in 2017.

“Our house was burned down and the Myanmar military shot dead one of my younger brothers. That’s why we fled to Bangladesh,” he said.

Fled to Malaysia

Meanwhile in Malaysia, Shahidullah Mohd Hosein, said his parents paid smugglers to help him leave a crowded refugee camp in search of better opportunities abroad.

Shahidullah lived in the Kutapalong refugee camp in Bangladesh after his family fled the prosecution in Myanmar. His family and about 1 million other Rohingya live in camps and settlements in and around Cox’s Bazar.

Shahidullah said he had no future in the camp.

“There are a lot of groups who kidnap people to demand ransom, and if the family of the kidnapped person does not pay, they threaten to kill that person,” Shahidullah, 29, told BenarNews.

He said groups have burned shelters in the crowded camps at night, leaving families homeless.

Shahidullah said he reached out to a syndicate to arrange passage to Malaysia. Before long the syndicate demanded his mother pay 500,000 Bangladeshi taka ($4,565) to transport him to Malaysia. He arrived in Malaysia in September 2023.

“I did not know how my mother was able to get the money. But after a few days I was sent to a boat with around 100 other Rohingya.

"It took us one month and some trekking to get us to Malaysia. We had no food throughout the journey and could only eat when we were on land," he said, adding that the group had to resort to eating leaves while trekking through jungles.

Shahidullah's journey ended last September in Ampang, near Malaysia's capital of Kuala Lumpur, where he has been housed by the Rohingya expatriate community.

In Bangladesh, a Rohingya woman has returned to a refugee camp after her attempt to travel to Myanmar for an arranged marriage led to spending more than a year in a Myanmar prison.

Halima Khatun saw her father killed by Burmese troops in Myanmar’s Rakhine state on Aug. 25, 2017. Her mother took her and two sisters across the border where they sheltered at a Bangladesh seeking shelter in the Teknaf refugee camp.

Halima, who was 18 at the time, said she fled the camp in late 2022 to travel to Malaysia assisted by human traffickers. Instead, she spent 13 months in prison after being arrested by Myanmar authorities when the boat’s engine broke down during the sea voyage.

“My family was unable to trace me during those 13 months. They assumed I had drowned in the sea or died anyhow,” she told BenarNews during an interview.

Following her release from prison, Halima returned to Bangladesh in February with assistance from Myanmar relatives.

“My marriage to Habibur Rahman, a young Rohingya guy in Malaysia, was planned. He was the one who attempted to utilize the ‘Dalal’ syndicate to get me there,” she said. The term means brokers.

“One of the brokers involved in my journey to Malaysia was a Rohingya living in Myanmar; another was a local Bangladeshi,” Halima said.

The traffickers demanded 800,000 taka ($7,289) as payment for transporting her to Malaysia.

She was traveling with several Rohingya men and women, as well as some Bangladeshis.

“After leaving Shamila [a Rakhine state village], we stayed on that boat for 22 days before moving on to another small boat for two days and two nights. Then, as the boat [engine stalled], the sailors rushed away.

“Then the ‘military’ arrived and rescued us. After that, a police car drove all of us to a place where we were for 12 days,” she said.

Sentenced to two years in a Myanmar prison, Halima spent 13 months incarcerated.

About three weeks ago, Halima paid a broker fee to cross the Naf river by boat and return to Bangladesh.

Halima said the man who promised to marry her had already married another Rohingya girl from a camp in Bangladesh and took her to Malaysia.

Abdur Rahman in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, Ahmad Mustakim Zulkifli in Kuala Lumpur, Nurdin Hasan in Banda Aceh, Indonesia, and John Bechtel in Washington contributed to this report.