People in the Deep South would like you to know that they are not so different from people in other parts of Thailand.

They care about their family, their faith, and their culture. And they want to live a dignified life and live it in peace.

The Deep South is a region along the Thai-Malaysia border comprising the provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala, and four districts of Songkhla province. It is distinguished by poverty, a separatist insurgency that has dragged on for decades, and the Melayu culture, of which Islam is a central part.

Here, a dozen residents of the southern border region talk about their struggles and their aspirations. A BenarNews correspondent from Bangkok interviewed them from Aug. 29 until Sept. 2, while traveling through the Deep South.

The 23-year-old recently graduated from a vocational college, where she was studying Chinese.

“I would like to speak many languages,” Nureta Mani says.

She works at a co-operative in the Barahom community in Maung, a district of Pattani province.

Her dream is to become a tour guide in southern Thailand.

Mohammad Marangoa, 35, listens to music on his phone as he walks to the morning market near his house.

He says he has mental health issues and so has not been able to find work. But music and morning walks help him.

Provinces in the Deep South are among the poorest in the country, with poverty rates of 34 percent in both Pattani and Narathiwat, according to a 2019 World Bank report. The nationwide poverty rate is 6 percent.

Every morning starting at dawn, Samuni Meandi, 27, works at a rubber plantation in insurgency-stricken Narathiwat province.

“But I barely make do with a living,” she says, adding that her earnings are uncertain because of the up-and-down prices for rubber products.

Buho Maming says she enjoys chewing beetle nut every morning.

At 86, she does not follow the news about the insurgency.

“I am not in touch with all that,” she answers, shaking her head gently when asked about recent coordinated attacks by suspected insurgents across the Deep South.

She was more than 20 years old when BRN, the most powerful separatist group in the region, came into existence in the early 1960s.

Prapat Chindanusan, a chief temple supervisor, advises visitors on how to pay homage to Chinese gods and goddesses at the Lim Ko Niew shrine in Pattani town.

“People of all faiths live in peace and harmony in Pattani. The differences are not the reasons for violent acts,” the 63-year-old says. There is also a small Chinese-Thai population, which came to settle here hundreds of years ago, with its own culture.

Yateng Waehama, 64, owns a small community food shop outside Pattani town.

He says he has no interest in politics.

“Politics? Don’t get me started,” he says, and shakes his head.

Asmawati Mabae, 34, works at a local government administration office in Narathiwat.

She says it is hard for young people in the Deep South to be secure about their future because of a lack of opportunities in the region, so many go to neighboring Malaysia in search of jobs.

Youth unemployment is high in Thailand’s southern region compared to the north, though there are no government figures.

First Lt. Chamnan Sengtub commands the 4305th Ranger Company in Koke Po, a district in Pattani.

“Our job is to protect people in this area. The insurgents are not from this neighborhood. We befriend the local residents and have a good understanding with them,” he says.

One of his men was killed in a 2020 roadside bombing. Since the insurgency re-ignited in 2004, more than 7,000 people have been killed and 13,500 others injured in violence across the region, according to Deep South Watch, a local think-tank.

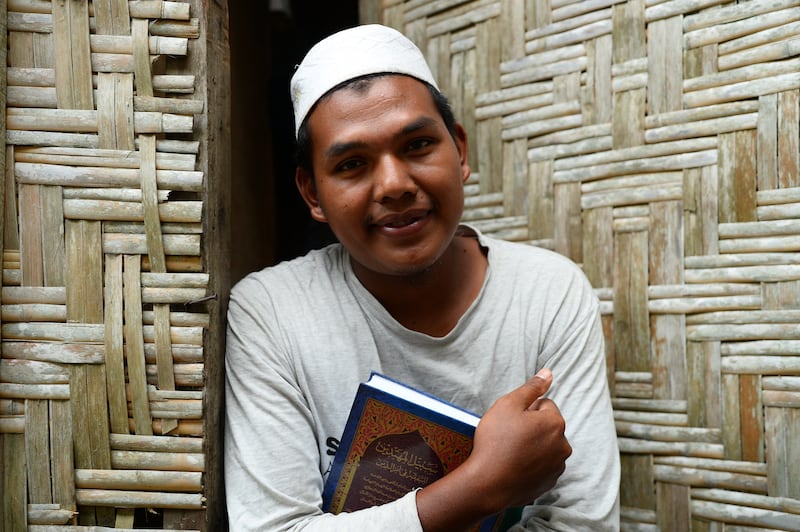

Hassan Tetae, 26, has been enrolled in Islamic studies at Ululumul Islamiyah Pondok, a school in Nong Chik district that teaches abut the Koran and Melayu culture. He started studying there at the age of 16 to “learn the path of Allah.”

He says he wants to have “a job, any general job would do” in the near future.

Koreyo Latae, 41, comes to pray at the historic Krue Se Mosque after selling chicken satay at the local market.

“The sales reduced by half since the violence last month. It was already bad since the COVID outbreak,” she says.

In mid-August 2022, insurgents targeted 17 spots in a coordinated attack in which one person was killed. No one claimed responsibility for the attack.

Charif Sobhanalle, 27, a student at Prince of Songkla University, helped organize the Deep Salt Exhibition in Pattani’s historic Chinatown to portray the “other side” of the province.

The exhibition includes arts, cultural heritage, and sea salt, a local product that many farmers depend on for their income.

“Deep inside, there is beauty in all cultures and people, including Buddhists, Muslims and Chinese,” he says.

Ni-ae Tuwaegaji, 26, is a third-generation salt farmer.

Salt farms in Pattani province are smaller in size than those in central Thailand, but the salt has a unique “sweet” taste due to the region’s geography.

“I’m afraid, one day salt farming here may disappear due to climate change and other issues,” he says.

Mariyam Ahmad, a BenarNews correspondent based in Pattani, contributed to this report.