The sister of Somkiat Srimaungko expressed a bittersweet joy as she gazed at his ashes.

Somkiat had finally come home to Thailand, three years after he died on Benjina, an Indonesian island that became notorious in 2015 as a symbol of modern-day slavery. In September, his sister traveled to the island to oversee his cremation and bring home the ashes.

His was the story of a Thai man who was freed along with hundreds of other enslaved Southeast Asians, but whose life was cut short only a month later while he was caught up in a bureaucratic tangle that delayed his homecoming.

After his death, identifying and repatriating Somkiat’s remains was a long process, rights groups said, underscoring the difficulty faced by volunteers seeking to exhume the bodies of up to 200 fishermen from across Southeast Asia believed to be buried in common graves on Benjina and nearby islands.

“I wish those other corpses there were exhumed and returned home, like my brother, no matter whether they are Thai, Laotian or from Myanmar,” Suksan Srimaungko, Somkiat’s sister, told BenarNews.

Her mind drifted back to the others still buried on Benjina, as she spoke to Benar during a religious service last month for Somkiat at his hometown in Karb Choeng, a district in northeastern Surin province.

She was referring to fishermen who worked on Benjina and other remote Indonesian islands, where more than 3,000 fishermen were freed in April 2015, after a covert investigation exposed horrific abuses in Thailand’s lucrative seafood industry.

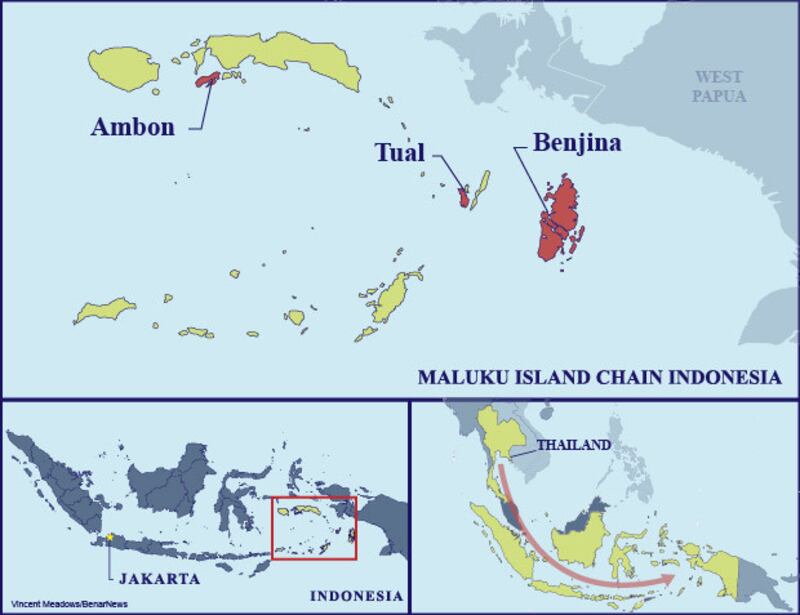

Benjina became the focus of investigations when a Thai human rights group teamed up with journalists and documented labor misdeeds, including allegations from fishermen that supervisors on ships tossed bodies into the sea to be devoured by sharks. The island, part of the Maluku chain, is about 2,900 km (1,800 miles) east of Jakarta.

Volunteers had interviewed area residents and witnesses and discovered multiple common graves, according to Patima Tungpuchayakul, director of the Labor Rights Promotion Network (LPN). There were 97 graves on Benjina, as well as 24 on Ambon and 100 on Tual islands, she said.

But she struggled to explain why – three years after the world caught a glimpse of appalling abuse of workers in the multibillion-dollar Thai fishing industry – rights advocates still could not get permits to exhume bodies.

“Ninety percent of the crews used fake documents, different names on their seamen’s books,” Patima told BenarNews. “It is hard to verify.”

A fisherman’s journey

She said Somkiat died on Benjina on May 4, 2015, a month after his fellow fishermen from rural villages in Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand and Laos were liberatedfrom the island, where they had endured many years of traumatic abuse that included being held in cages like slaves.

Five years ago, Somkiat worked on a Thai fishing vessel but, later on, wound up working for a Malaysian boat that went to Benjina Island, where he used a Cambodian name to hide his immigration status, LPN said.

He was alive when thousands of his fellow fishermen won their freedom in April 2015, and he wanted to go home, according to LPN.

During their investigations, rights advocates took photographs of a graveyard surrounded by tall grass and wild shrubs that, according to the Associated Press, entombed 64 fishermen who never came back home. AP was the news agency that broke the story about Benjina and earned a Pulitzer Prize for it.

The pictures showed wooden plaques painted in bright yellow, blue or white that identified the bodies below. Each marker showed the fisherman's name, birth date, home town, seaman's book number, the name of the vessel he worked on and his date of death.

Rights advocates also interviewed fishermen who said they helped bury their friends who had used fake Thai names.

Patima said advocates met Somkiat on Benjina, but his repatriation was delayed because authorities had difficulty confirming his identity.

On May 4, 2015 Somkiat fell to his death from a fishing vessel, according to Indonesian authorities.

“Somkiat told us he wanted to go home, but he couldn’t because his seaman’s book had identified him as a Cambodian named Chaiya Bounsam. He couldn’t leave because of the inaccurate document. He died a week later,” Patima said.

“We don’t know how long it takes but on behalf of the dead, we would like people to find their relatives,” she said. “There are too many who died. I wish the government could promote better working conditions for fishermen.”

Temporary ban

After thousands of fishermen were freed from captivity, Indonesia ordered a temporary ban on most fishing, clearing out foreign trawlers that harvest billions of dollars of mackerel, tuna, grouper and squid from Arafura Sea, which draws illegal fishing fleets from Southeast Asian nations.

But as a result of the moratorium, dozens of foreign boats docked in Benjina and about 1,000 migrant workers were stranded onshore when they were abandoned by their boat captains.

Others had been trapped on the islands for years after escaping into the jungle, rights advocates said. But, so far, only five Thais had approached them to help find their missing relatives, according to LPN.

Chairat Ratchapaksi, who worked on a Thai commercial fishing boat, corroborated the story of abuse and violence, telling BenarNews recently that up to 500 fishermen had escaped captivity and vanished into islets.

Chairat, who now heads the Thai and Migrant Fishers Union Group, said exhuming a grave in Indonesia would be costly: about 150,000 baht (about U.S. $4,500).

Relatives might be able to help verify the remains, but they often couldn’t identify the fishing vessels where their relatives worked on and what names were logged in their seaman’s book, Chairat said.

“There must be some clue before a grave can be dug for DNA testing,” he said. “To bring out remains or ashes improperly is illegal. … We must find a starting point before we could help.”

The government was ready to help bring back the ashes of those who died, Somboon Traisilanan, a director at the Thai Ministry of Labor, told BenarNews.

“I saw markings of names and nationalities, but who knows if the grave with Thai name markings may contain a Cambodian? They used false identities before 2015,” Somboon said.

The abuses spurred Thailand’s military government to promise a new national registry of illegal migrant workers, including those working in the fishing industry.

But in a report in March, the U.N.’s International Labor Organization (ILO) said that unfair practices and deception still existed in the nation’s fishing industry.