Sulak Sivaraksa was born soon after the Siam Revolution, when Thai intellectuals and members of the elite joined forces with disaffected army officers to stage a bloodless coup that ended nearly seven centuries of the monarchy’s absolute rule.

The revolution they launched before dawn on June 24, 1932 did not abolish the royal institution outright or turn the kingdom into a republic, but transformed it into a constitutional monarchy.

The life of Sulak, a widely respected and outspoken Thai academic, has spanned the nine decades since that pivotal moment in Thailand’s modern history. During that time, at least a dozen successful military coups have postponed the Thai people’s quest for full-fledged democracy.

“Before 1932, the monarch was above the law, and he was the only one. After the 1932 [revolution], everybody became equal, everybody was under the law, and that was the first victory,” Sulak, a noted scholar of Buddhism, told BenarNews in an interview this month.

“In these 90 years, we are currently [at] the lowest point,” said Sulak, who walks with a cane that once belonged to Pridi Banomyong, the leader of the 1932 revolution and co-author of Thailand’s first constitution.

Meanwhile, the monarchy remains powerful and deeply entrenched in Thai society, shielded by a strict anti-royal defamation law.

Sulak has been charged and prosecuted multiple times under Lese-Majeste, a law where the smallest perceived public slight of royals can land you in jail, such as "liking" and sharing a controversial profile of the king via Facebook.

The government of Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha, the former junta chief who led the country’s last coup in 2014 and has stayed in power since, has used the law to go after young pro-democracy activists.

“Gen. Prayuth claims this is a democracy, but it’s a sham democracy because he is a soldier who never left his office. He is still in power eight to nine years later and does not want to step down,” Sulak, 89, told BenarNews.

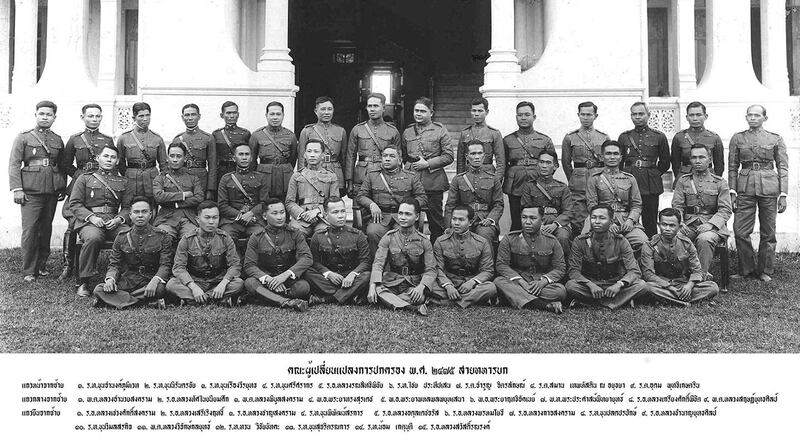

Royal Thai Army soldiers who participated in the Siam Revolution against King Rama VII in June 1932. [Courtesy Thai Parliament Museum]

The Siamese Revolution started the so-called constitutional era in the Southeast Asian nation, and for a brief, shining period, Thailand had “full democracy,” Sulak said.

Within a year of the revolution, however, Phraya Manopakorn Nititada, the first prime minister of Siam, was ousted in a military-led coup in June 1933, just two months after he took power for himself, dissolving parliament.

After yet another military takeover in 1947, “the coup leader praised the monarch, who was until then still under the constitution. They turned the monarch to God-like and above the constitution because they thought only the monarch could fight against the communists,” Sulak recalled.

The Thai monarchy has since become irreproachable. The 1932 revolution, on the other hand, is barely mentioned in school history books these days. The day is celebrated in a hushed manner, and few memorials survive.

“The royalist-military nexus is a legacy of the long and unfinished transition from absolute monarchy,” Thongchai Winichakul, a professor of Southeast Asian history at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, wrote in an article for Nikkei in 2020

“The genuine constitutional democracy promised by the People’s Party, the backers of the 1932 revolution against King Prajadhipok, has never really been achieved.”

According to Thongchai, the monarchy “achieved uncontestable moral authority” by the 1970s.

“That influence was subsequently converted to political dominance, which endures to this day,” he added.

Thai King Maha Vajiralongkorn attends a foundation stone-laying ceremony for a monument in honor of his late father, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, in Bangkok, Dec. 5, 2021. [AP Photo]

In 2017, a small brass plaque laid into the middle of the road at the Royal Plaza in Bangkok that commemorated the Siam Revolution went missing. It was replaced with a similar one bearing pro-monarchy inscriptions.

The Siamese Revolution "was the beginning of the call for democracy and the start of the fight for democracy. It was precarious because those involved in the 1932 revolution risked their lives," Arnon Nampa , a prominent pro-democracy activist, told BenarNews.

Arnon, 37, is among activist leaders who have been charged with Lese-Majeste. In their struggle to bring full-fledged constitutional democracy to Thailand, he and his fellow activists are willing, too, to risk losing their freedom or lives for it, he said.

True friend of monarchy

Sulak, who was born into a wealthy Thai-Chinese family in March 1933, studied history and literature at the University of Wales in Britain in the 1950s. He returned to Thailand in 1961 and taught at Bangkok universities.

Sulak founded and edited Social Science Review, an intellectual magazine published in Thai, which played a crucial role in the student uprising that led to the overthrow of the military dictatorship in 1973.

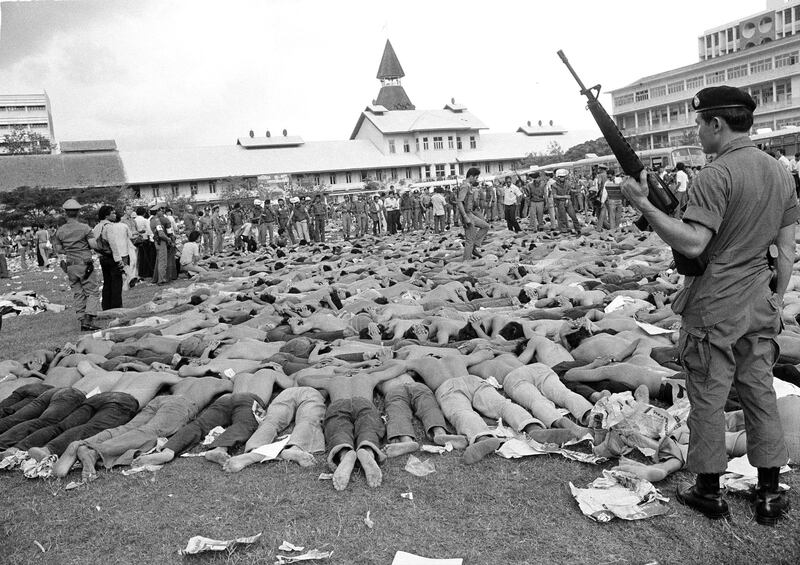

In 1976, Thailand experienced its bloodiest coup, as hundreds of students were killed and thousands jailed. The military burned the entire stock of Sulak’s bookshop, a hub for intellectuals and activists, and issued a warrant for his arrest. He was abroad then and lived in exile for the next two years.

Sulak also helped start many indigenous grassroots organizations. For his social activism, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award, also known as the Alternative Nobel Peace Prize, in 1995.

A policeman stands guard over leftist Thai students on a soccer field at Thammasat University, in Bangkok, Oct. 6, 1976. Police stormed the campus to break up a demonstration by thousands of leftist students protesting the return of former military ruler Thanom Kittikachorn. More than 40 people were killed and over 150 injured during the raid. [AP Photo]

Sulak, who considers himself “a true friend” of the monarchy, has been jailed four times and accused of defaming the Thai monarchy five times.

The monarchy “is a very touchy subject in this country. Either you hate it, or you admire it blindly,” Sulak told a panel discussion at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand in January.

“For me, it’s wrong on both sides. The monarchy, of course, is an institution represented by the present king, and the king is a human being. He has his weak points, his strong points, which we [should] try to understand,” he said.

“And with that understanding, perhaps, you can humbly suggest changing because the king, I’m pretty sure, will listen. And even with him, he cannot change everything himself,” Sulak said.

King Maha Vajiralongkorn, he noted, had recently granted him a 90-minute private audience.

“And his main concerns were three: Would the monarchy survive in this country, how would Buddhism operate in this country meaningfully, and thirdly, would democracy fit in with this country?” Sulak said.

At the other end of the social spectrum, Thailand’s young people give Sulak a glimmer of hope.

“Young generations understand Thailand. The structure is unfair; it benefits only the wealthy and influential ones and takes advantage of the poor,” he said during the interview at his home in Bangrak, a district of Bangkok.

“For me, democracy has to have freedom of speech, argument and disagreement, while respecting different opinions,” said Sulak, who has written more than 100 books on Buddhism, the Thai monarchy, and social issues.

In 2020, when massive, youth-led street protests sprang up against Prayuth’s government, Sulak shocked many people by attending several of the rallies.

“I’m only an old man, looking forward to young generations. I’ve seen young generations who are so brave to fight against dictatorship,” he said.

“I hope that Thailand, while celebrating 100 years of democracy, will go forward and not backward as is happening nowadays.”