Thailand’s plan to open a humanitarian aid corridor with war-torn Myanmar next month is facing skepticism from experts and aid workers, who say its limited scope and lack of engagement with ethnic minority forces means it is unlikely to have much impact.

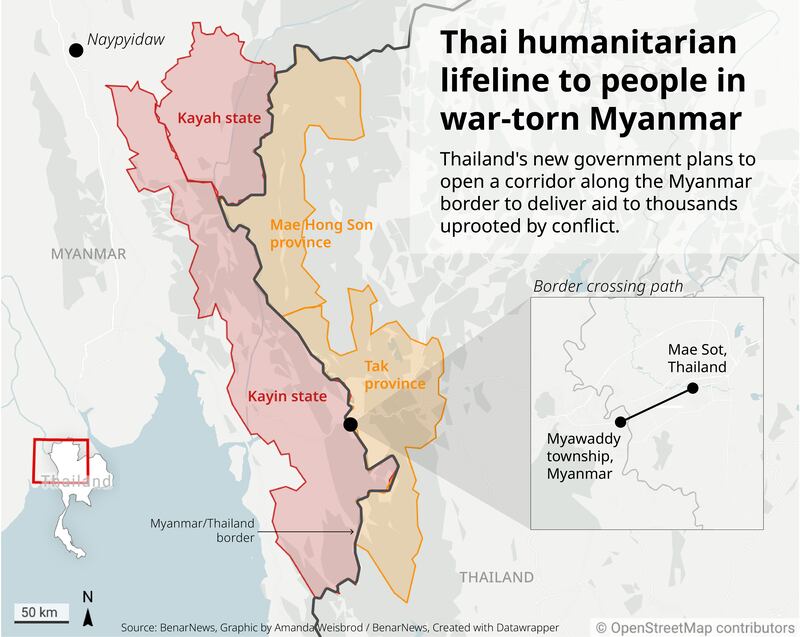

The initiative by the new Thai government will create a safe zone to provide food and medicine to displaced populations through the Mae Sot-Myawaddy border crossing, officials said. Foreign ministers from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) unanimously endorsed the plan in January.

Fierce fighting during Myanmar’s civil war, set off by a military coup in February 2021, has forced more than 2.7 million people across the country to flee their homes, according to United Nations estimates.

As of Feb. 19, more than 306,000 of them were in Kayin and Kayah states, along the western border of Thailand, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR.

The initiative will see the Thai and Myanmar Red Cross make aid deliveries under monitoring from the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management.

Initially, the humanitarian corridor will help about 20,000 internally displaced people, stabilize border trade, and complement ASEAN efforts to end hostilities, according to the Thai government.

More ambitiously, Bangkok hopes it will lay the groundwork for dialogue between Myanmar’s military junta, ethnic rebel forces and the shadow National Unity Government.

But whether the aid initiative will have such a far-reaching impact is far from clear, according to analysts.

“If Thailand truly aims to help Myanmar citizens, it is crucial to talk with all parties involved, including ethnic armed forces and the entire civil society, not just leave everything to the Myanmar Red Cross,” Lalita Hanwong, a Southeast Asian history lecturer at Kasetsart University, told BenarNews.

Thailand must do more than provide short-term assistance along the border if it wants to find a durable solution to Myanmar’s conflict, said Lalita, who also serves as an advisor to the Thai government on national security issues.

The opposition NUG, which is made up of ousted members of the elected government and other public figures, also cast doubt on the Thai aid plan.

“We acknowledge Thailand’s efforts to assist the people of Myanmar. However, effective collaboration with the ethnic resistance forces, including the National Unity Government, is imperative to aid those fleeing the conflict in Myanmar,” the NUG press office told BenarNews in a statement.

“This is due to the fact that the NUG and the ethnic revolutionary forces currently control approximately 60% of Myanmar.”

Thailand, which shares a 2,400-kilometer (1,491-mile) border with Myanmar, has hosted more than 90,000 refugees from Myanmar in nine temporary shelters since the mid-1980s.

Tak and Mae Hong Son provinces have seen the highest influx into Thailand of Myanmar nationals fleeing conflict, but Bangkok’s response so far has been limited to providing temporary shelter. Previously, humanitarian aid had come from private donations, while the government periodically pushed back refugees to discourage more from seeking asylum in Thailand.

The Thai government maintained close relations with the Myanmar junta under former Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha, an ex-general who as the army chief took power in a 2014 military coup but was voted out of office last year.

Over his nine-year reign, Prayuth's administration claimed to be pursuing a peaceful solution to the crisis across the border, but his government was regularly criticized for its accommodative attitude towards the Burmese military.

In June last year, Prayuth's decision to circumvent ASEAN's Five-Point consensus and hold direct talks with the Myanmar military caused a schism among members of the regional bloc.

The consensus, agreed to a few months after the 2021 coup, called for an immediate end to violence; a dialogue among all concerned parties; mediation of the dialogue process by an ASEAN special envoy; provision of humanitarian aid through ASEAN channels; and a visit to Myanmar by the bloc’s special envoy to meet all concerned parties.

“In the past, the government under General Prayuth and Thai security forces have had good relations with the Myanmar military, which is believed to have made Thailand cautious about taking significant actions for fear of losing this relationship,” Lalita said.

Dulyapak Preecharush, an assistant professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Thammasat University, said Thailand was taking a more proactive and coherent approach to Myanmar under Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin, whose government came to power last September.

“Under the previous administration, we lacked a strategic vision, putting us at a disadvantage compared to regional players like Indonesia.”

On the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Thai Foreign Minister Parnpree Bahiddha-Nukara last month outlined the rationale behind the aid initiative.

“The fear among the regional countries is Myanmar becoming increasingly fragmented and becoming an arena for major-power competition,” he said at a diplomacy dialogue on Myanmar.

“As we see it, humanitarian assistance leads to humanitarian pause and humanitarian dialogue.”

The humanitarian corridor would also help people in both countries normalize full trading activities, Parnpree, who is also deputy prime minister, said earlier this month while visiting the Thai-Myanmar border.

Pornsuk Kerdsawang, an aid worker from Friends Without Borders Foundation, based in Thailand’s Mae Sot district close to the Myanmar border, welcomed the Thai initiative, but she said for it to be meaningful it must include provisions to end hostilities.

“The reason for the displacement in Myanmar is due to attacks by the Myanmar military, especially using heavy artillery and air strikes,” she told BenarNews.

Pornsuk questioned whether the Myanmar Red Cross could genuinely access populations in need, given the Myanmar military controlled many of the delivery routes.

“What Thailand can do is to consult with Myanmar’s civil society organizations that are helping people,” she said. “Plan and design the aid together, which will likely meet actual needs.”

Ruj Chuenban in Bangkok contributed to this report.