Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has retained power via yet another lopsided election after a boycott by the main opposition party turned it into a no-contest.

The victory of Hasina and her Awami League party at the polls on Jan. 7 clinched her government’s fourth consecutive term in power and fifth overall.

The 76-year-old is the world’s longest-serving female head of government and one of two women who have served as leader of Bangladesh. And barring circumstances that would prevent her from fulfilling her duties or require her to step down, she would spend 25 years in the office of prime minister should she last through her next term.

“If I’ve made any mistakes along the way, my request to you will be to look at the matter with the eyes of forgiveness,” Hasina told the nation in a televised address on Thursday night, the eve of the end of official campaigning for Bangladesh’s 12th general election.

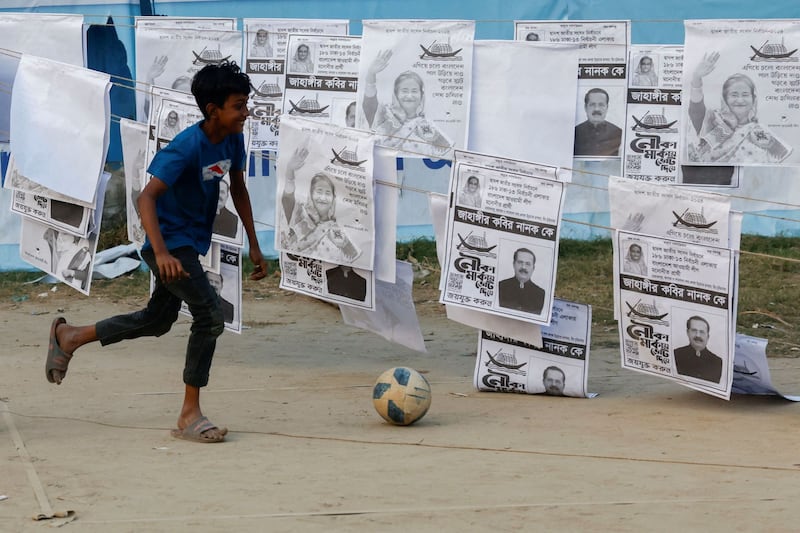

“If I can form the government again, I will get a chance to correct the mistakes. Give me an opportunity to serve you by voting for the ‘Boat’ in the Jan. 7 election,” she said, referring to her party’s symbol.

Some of her fans and ardent supporters call Hasina, the daughter of the country's founding father, the "mother of humanity." But while leading this South Asian nation of 170 million on a track of mostly robust economic growth since 2009, she and her government have not been so forgiving to its critics.

In recent years, she has drawn international scrutiny for an increasingly authoritarian style and record on human rights and free speech tainted by allegations of enforced disappearances and arrests of journalists and critics.

In the weeks and months leading up to Sunday’s election, the police and security forces rounded up and jailed tens of thousands of members of the rival Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), which had been staging protests over the election.

A politician’s life forged by trauma

Hasina’s career as a politician began in the early 1980s, after assassins’ bullets thrust her into politics.

Hasina formally took over the Awami League six years after her father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, her mother and other family members were gunned down during a coup in 1975.

Hasina narrowly escaped being caught in that bloodbath. By mere luck, she and her sister were traveling abroad during the assassination of Rahman, who had led the Bangladeshi independence movement in the 1971 war against Pakistan.

All these decades later, Hasina’s voice unmistakably shakes when she often refers to her father’s killing in every public speech.

“I stepped into politics to fulfill my father’s dream,” she said in her speech to the nation on Thursday evening.

Hasina has also talked about carrying on with the legacy of her late father, who to this day is widely revered as a national hero in Bangladesh’s struggle for independence.

But Rahman, who was also known as Sheikh Mujib, slid into his own brand of autocratic rule after becoming the leader of the young country.

A year before he was assassinated, Rahman banned all political parties and the majority of the press, and formed a Chinese Communist Party-style one-party system called Bakshal.

"Domestically, she has propagated a suffocating cult of personality around Mujib; an enormous portrait of the 'Father of Nation' looms over our conversation, and his mustachioed visage adorns every public office and website," read a recent profile of Hasina published by Time magazine.

Her critics allege today that she has established a de facto Bakshal 2.0.

But Hasina ascended to power on a more democratic path.

She had earlier stated a wish to retire at age 60, but as she begins a fifth term, her succession is uncertain; it is no longer clear whether her son, Sajeeb Wazed – once her obvious heir – will inherit her power. Hasina’s sister, Sheikh Rehana, frequently seen at election rallies, is rumored to be her potential successor.

‘People’s Leader’

In 1981, Hasina returned to Bangladesh from exile in India shortly after being elected president of the Awami League. At the time, the country was ruled by President Ziaur Rahman, a military general who a few years earlier had founded the BNP.

Rahman was killed in a coup days after Hasina returned, allowing another army general, Hussain Muhammad Ershad, to grab power.

Hasina collaborated with the BNP’s Khaleda Zia – Ziaur Rahman’s widow, who would later become her bitter foe – to oust Ershad in a civilian mass movement. For her role in the movement, Hasina was affectionately dubbed the “Daughter of Democracy” – an honorific that few Bangladeshis use today in referring to her.

In 1996, when the BNP held an election defying Hasina’s demand that a neutral caretaker government oversee the polls, she led opposition parties to boycott the election.

The BNP returned to power virtually unopposed – similar to her latest victory on Jan. 7 – but the Awami League’s constant street agitations forced Zia’s government to resign and call for fresh elections under a newly constituted caretaker system.

In that election, Hasina became prime minister for the first time.

Her first tenure was defined by the rise of party-affiliated gangsters, which cost her popularity later. She also went against the military by striking a peace deal with ethnic insurgents in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The former rebels now say they felt betrayed, and sporadic violence still continues, but the region is largely more peaceful today than in the turbulent era of the 1980s.

The opposition years

Known for its fiery and aggressive political tactics, Hasina’s Awami League was a relentless force even when it was relegated to the opposition again in 2001. The frequent nationwide strikes and road blockades called by the party kept the BNP government on the back foot.

She successfully seized on ills of the then-government – from rampant corruption allegations and the emergence of post-9/11 Muslim extremism to rising inflation – and courted the sympathy of Western nations and a large section of the local press and civil society, all of whom she routinely derides today.

Hasina’s life has also been marked by direct threats of violence against her.

According to the Awami League’s tally, she has survived as many as 19 assassination attempts, the most recent of which occurred in 2004. In that incident, she narrowly escaped a grenade attack that killed more than a dozen people.

Although a Muslim extremist group was believed to have executed the attack, Hasina has consistently attributed responsibility to the BNP government.

When elections approached in 2006, Hasina’s party again boycotted the polls, claiming that the BNP manipulated the caretaker system. Bloody street battles that ensued enabled the military to intervene in 2007, and she took a victory parade. But the new military-backed government placed both Hasina and Zia in jail on corruption charges.

Both were released a year later to contest the election in 2008, which Hasina won in a landslide.

Hasina’s new term faced the first setback when, in February 2009, members of the country’s border force staged a mutiny against their superior officers from the military, which threatened the prospect of another coup.

In the years that followed, Hasina embarked on a campaign to tame the powerful, meddlesome army through massive defense budgets and other largesse and by rooting out perceived adversaries.

Hasina contended with challenges from the faith-based Jamaat-e-Islam party, allied with the BNP. Her government established a tribunal to prosecute Jamaat leaders for alleged collaboration with Pakistan in 1971 war crimes.

The trials, which were widely criticized as flawed by human rights organizations, the U.N., and the U.S., inflamed and polarized Bangladeshis along the political spectrum, and wound up delivering death penalties for many of the accused.

A separate Muslim pressure group, Hefazat-e-Islam, also emerged in 2013 to demand blasphemy laws and harsh punishment for atheists. She was accused of subduing them through a combination of crude force and largesse.

Enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings shot up during that period, according to rights groups. However, government officials have steadfastly pushed back against such criticism.

“These [allegations] are not true,” Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal told BenarNews at the time. “We take every reported case of so-called abduction seriously.”

The BNP-led opposition boycotted the 2014 election because Hasina’s government removed the provision of the election-time caretaker government – a system that had been established through her insistence – and she returned to office effortlessly.

Hasina is also widely credited for tackling the problem of Muslim extremism in Bangladesh, especially after groups such as the Islamic State and al-Qaeda carried out killings of secular writers and bloggers in the country. However, the country's deadliest-ever terrorist attack, an overnight siege of a café by pro-IS militants that left at least 20 dead, occurred under her watch.

Meanwhile, allegations about security forces carrying out extrajudicial killings kept surfacing. An ostensive anti-drug drive in the election year of 2018 left more than 400 people dead, according to local and international rights groups.

It was in 2018 that the government relaunched an internet law and made it harsher. The Digital Security Act would go on to target journalists and social media speech disproportionately, stifle a climate for unfettered expression and lead to arrests of critics of her government.

Also that year, when hundreds of thousands of schoolchildren took to the streets for better road safety, security forces dispersed them brutally.

Khaleda Zia, her arch-rival, was jailed on contested graft charges before the election and later paroled for humanitarian reasons. Since then, she’s remained publicly silent on politics, and despite medical advice for overseas treatment, the government has denied her travel.

In the 2018 election, Hasina still refused to step down to make way for a caretaker government, but BNP, the beleaguered leader of the opposition, agreed to participate. The election returned improbable results, with her party winning over 95% of the electoral seats amid widespread allegations of ballot stuffing.

Under Hasina’s leadership, Bangladesh, boosted by its robust ready-made garment sector and remittances sent by millions of expat workers, became one of the world’s fastest-growing economies until the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in 2020.

During this period, per-capita income nearly tripled, and in 2015, the country started transitioning from a least developed to a developing country, a process now set for completion in 2026.

Hasina's government also launched a series of China-backed mega-infrastructure projects costing tens of billions of U.S. dollars, which also helped spur the growth, experts say.

However, the pandemic’s impact on Western countries, key importers of Bangladesh-made textiles, dealt a blow to this economic growth.

Meanwhile, the Russia-Ukraine war caused oil and grain prices to soar, drastically increasing living costs and pushing many middle-income families into poverty.

The significant devaluation of the taka against the U.S. dollar eroded these families’ savings.

Bangladesh’s foreign reserves have dwindled from U.S. $40 billion to a critical $17 billion, barely covering three months of exports, with the potential for further decline as the government begins repaying substantial foreign loans next year.

Many predict that the future looks bleak under her government.

"To maintain its grip on power when the economy is struggling and its support is falling, the AL [Awami League] will likely have to engage in higher levels of state control and coercion," the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based think-tank, said in a report released last week.